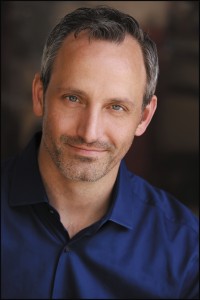

Jonathan Kellerman, the bestselling author of more than forty crime novels, is known to mystery-lovers everywhere. With a doctorate in psychology, Jonathan has applied his knowledge not only to his novels, but to those he has co-written with his wife Faye, and s on, Jesse. All three are bestselling authors. He has also written children’s and nonfiction books.

on, Jesse. All three are bestselling authors. He has also written children’s and nonfiction books.

He’s won the Goldwyn, Edgar, and Anthony Awards, and has been nominated for a Shamus Award. Along with the late Sue Grafton’s “Alphabet series,” Jonathan’s acclaimed Alex Delaware series is one of the longest running on the literary landscape.

Jonathan’s latest novel, Night Moves, opens with a baffling situation. How and why does the faceless, handless body of a murdered man wind up in the home of a suburban family? The man clearly was killed elsewhere; there’s no sign of blood or violence found in the house. Alex Delaware and his detective partner, Milo Sturgis, must deal with a horrified family.

Soon, another murder occurs, and it’s clear this suburban enclave has plenty of suspicious characters, secrets, and deceit. The novel becomes a taut police procedural as Alex and Milo sift through a tangled web of greed, betrayal, and treachery.

The dialogue in Night Moves is crisp and realistic. Talk to us about dialogue.

I learned to write dialogue from my wife. Faye’s like Rich Little: she’s a great mimic. Even her first novel had superb dialogue. The thing with dialogue is it has to sound like people talking, but of course, it cannot because the way people really talk is boring, repetitive, circular and filled with uhms and ahs.

In addition to writing, I paint. Actually, it’s what I’m naturally better at doing. I realize that both painting and writing are forms of trickery. In painting, I’m simulating three dimensions using two. It’s the same with writing. It’s a form tromp of d’oeil.

Having a doctorate in psychology and practicing clinical psychology, what made you turn to writing fiction?

I’ve been writing fiction since the age of nine. However, I never saw writing as a career. I was also attracted to science—and to music and art, which I continue to pursue. In college, I got a gig as an editorial cartoonist for the campus newspaper. That led to opportunities to write for the paper–columns, reviews, and straight reporting. I ended up as an editor, and essentially, had a dual identity: journalist and student of psychology. In my senior year, I won a literary prize and got an agent.

But that didn’t end my desire to become a child psychologist. While in grad school, I continued to write, publishing scientific articles, nonfiction, a short story, and my doctoral dissertation. At the same time, I was writing novels at night in my garage. Eventually, my first novel was published in 1985.

I loved being a child clinical psychologist and was reluctant to give up my practice. So, I continued to write and treat patients. I published five bestselling novels while in full-time practice, but eventually, working two jobs became untenable. In 1990, I became a full-time novelist.

But for five years, you had a dual identity: practicing psychology and writing fiction? What was that like?

It was rather manic. At that point, we had three kids and Faye and I were both writing. Thankfully, she’s Superwoman and handled so many things. I had three associates and we had a large practice in child psychology. I’d work all day seeing patients, then come home and spend time with my own kids, and at eleven in the evening, I’d go out to my office-garage and write for two hours. It’s the same routine I followed as a failed writer [Laughter]. Occasionally, if I had a cancellation, I’d sit down and work on my book. I was in my thirties and had lots of energy. I probably couldn’t do it today.

Do you ever miss your daily work as a psychologist?

At this point, I really don’t. I’m the kind of guy who loves something while I’m doing it, and then I’m able to move on. I loved helping kids and gave it up reluctantly. After leaving the practice, I did consulting and teaching, so I eased myself out of it.

As a psychologist, my time was strictly scheduled months in advance. As a writer, my time is very flexible and unstructured. I really enjoy the freedom I now have.

in Night Moves, a specific crime propels the novel, but the story also serves as a vehicle for commentary about life. Tell us about that.

I think that’s just naturally the way I see the world. Being a psychologist informs my writing. For example, as someone who worked with children in oncology, an event like a terrible cancer diagnosis can become a catalyst for unlocking all kinds of other issues. That awareness colors my writing in the sense that a specific crime can open up a Pandora’s box of reactions and situations. Every crime impacts people, and trauma can bring out the best or worst in them, whether in a novel or in real life.

Night Moves has an extraordinary number of plot twists and developments. How do you construct a novel that’s both complex yet linear, so the reader easily follows the storyline?

That’s the major challenge in writing a novel. I think my academic training helps in that regard. I learned how to organize. I outline my novels by jotting down impressions, ideas and notes. Then, I progress to creating a general outline, and then a chapter-by-chapter outline.

I hold off on the actual writing until I have a sense of control over my material. Ironically, I rarely consult the outline and often find the finished book is quite different from what I had plotted.

However, the outline helps me structure things. It’s like an architect’s plans for designing a house. The writing itself becomes the interior decoration, and it’s the fun part. Then of course, there’s the rewrite, which refines and sculpts the manuscript to a finely-honed edge.

Alex Delaware had a difficult childhood. As psychologists, both he and you know the indelible effects of the past on current functioning. How does Alex’s past affect his present life?

Alex evolved as I got to know him better by writing books about him. When I wrote the first one, When the Bough Breaks, which was published in 1985, I never thought I’d get it published, let alone that it would become the first book in a successful series. I learned about Alex, along with my readers, and things began falling into place.

I parcel out his childhood and his personal history very judiciously. In some novels, he’s a protagonist; in others, he’s a consulting psychologist. Of course, his past has impacted his interest in psychology and his wanting to set certain things right.

I know you’ve been asked this question before, but how much of Jonathan Kellerman exists in Alex Delaware?

I think the author is in every character.

It took five years for an Alex Delaware novel to be published, and I realized I’d be best off writing about what I knew, which was clinical child psychiatry. So, there are career parallels. But, Alex is younger than I am; he’s thinner; more athletic; and much braver than I am. I’m a coward, which describes many crime writers. We write about things which frighten us.

I’m married with four kids; he’s single with no kids. He’s free to engage in high-risk behavior while I’m not. There’s a lot of me in him and in Milo, and in the bad guys, too. In a sense, all fiction is autobiography.

I know you’re a huge fan of Ross Macdonald. Will you talk about that?

It was serendipitous that I discovered him. One day as I was driving to Children’s Hospital, I passed a bookstore with a sign that read, ‘Books on Sale, Cheap.’ I went in, browsed around and found a book called The Underground Man by Ross Macdonald. I’d never read any of the hardboiled writers, but the flap copy was really interesting.

Reading the book blew me away. He was a brilliant writer who wrote about psychopathology in Southern California, and his books were beautifully written. I thought, ‘maybe I could do that.’

In fact, Ross Macdonald’s style informed my writing, When the Bough Breaks so much so, that my editor said, ‘This is really great but there’s a little too much Ross Macdonald here. Try to establish your own voice a little more.’ That’s what I’ve done.

If you could meet any two fictional characters from all of literature, who would they be?

I’d love to meet Edmond Dantes of The Count of Monte Cristo because he was so interesting. He evolved from the depths of despair to triumph. I’d also love to meet Watson from the Sherlock Holmes stories. I don’t think Sherlock would be very good company, but Watson was a doctor and highly intelligent. I think I could relate to him better than I could to Sherlock Holmes.

Will you complete this sentence: writing fiction has taught me__________________.

Writing fiction has taught me humility in the sense that I may think I know something about people, but they’re always unpredictable. And, I’m humbled by the realization that often occurs when I’m writing a novel and think I’ve done a good job, only to see the manuscript needs a ton more work to be done.

Congratulations on penning Night Moves, a tense, tightly woven novel that not only deals with crime, but as do all the Alex Delaware novels, addresses many compelling issues of contemporary life.

Mark Rubinstein is a novelist, physician and psychiatrist. His latest novel is Mad Dog Vengeance, a psychological suspense-thriller.

Patricia Cornwell is known to millions of readers worldwide. She has won nearly every literary award for popular fiction and has authored 29 New York Times bestsellers. Her novels center primarily on medical examiner Kay Scarpetta, along with her tech-savvy niece Lucy and investigator Pete Marino.

Patricia Cornwell is known to millions of readers worldwide. She has won nearly every literary award for popular fiction and has authored 29 New York Times bestsellers. Her novels center primarily on medical examiner Kay Scarpetta, along with her tech-savvy niece Lucy and investigator Pete Marino.

I’m occasionally asked why I write crime-thriller novels.

I’m occasionally asked why I write crime-thriller novels. The Foot Soldier, one of four finalists for the Benjamin Franklin Award in fiction, won the Silver Award for Popular Fiction.

The Foot Soldier, one of four finalists for the Benjamin Franklin Award in fiction, won the Silver Award for Popular Fiction. Anna Godbersen is the bestselling author of The Luxe series and Bright Young Things. Her new novel, The Blonde, is her first foray into adult fiction and is a compulsively gripping read. It re-imagines the life of Marilyn Monroe in a way that becomes a thriller/mystery with a truly amazing twist at the end.

Anna Godbersen is the bestselling author of The Luxe series and Bright Young Things. Her new novel, The Blonde, is her first foray into adult fiction and is a compulsively gripping read. It re-imagines the life of Marilyn Monroe in a way that becomes a thriller/mystery with a truly amazing twist at the end.