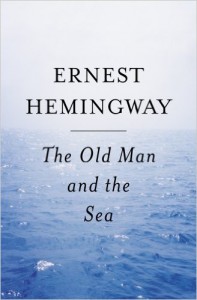

Okay, I admit to not having read many of the classics when I was a kid, and regret even more so bypassing these masterworks for all the decades I’ve been an adult. But there were a number I did read…you remember, all those assigned books we were forced to tackle in school. Among that number was The Old Man and the Sea.

This book, basically a novella, had rested on my bookshelf for years.

One day, it caught my eye and I decided to give it another read. My sole motivation was to see what had made it worthy of winning Hemingway the Nobel Prize.

The beauty and power of Hemingway’s prose, which was lost to me as a teen, now engulfed me with its spot-on magnificence, as Santiago’s character emerged in great depth, all within relatively few pages at the hand of this master.

As a man, I could appreciate the depth of the aged Santiago; and now understood his feelings about the sea, the marlin he caught, the sharks with whom he shared the waters, and I found a personal connection to his life and the lives of others as depicted in the novella.

As a novelist, I was struck to my core by the power and grace of Hemingway’s beautiful and economical use of language.

I knew the book had been wasted on me as a youth.

Since that day, I’ve re-read other classics. A few have left me as indifferent to them now as when they were assigned to me in high school; but many more have revealed themselves to the ” adult” me in ways I could never have imagined back in the day.

Why not pick up one such book yourself, and explore your own growth within its pages?

Let me suggest you begin with re-reading The Old Man and the Sea.