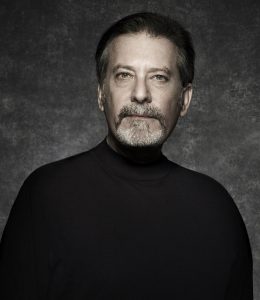

C. J. Box is the bestselling author of 17 Joe Pickett novels, four standalones, and a collection of short stories called Shots Fired. He’s won multiple awards including the Edgar, the Anthony, the Gumshoe, and the Barry. His books have been translated into twenty-seven languages.

J. Box is the bestselling author of 17 Joe Pickett novels, four standalones, and a collection of short stories called Shots Fired. He’s won multiple awards including the Edgar, the Anthony, the Gumshoe, and the Barry. His books have been translated into twenty-seven languages.

He lives with his family outside Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Joe Pickett, the protagonist in the series, is a Wyoming game warden who often finds himself embroiled in perilous situations for him and his family.

In The Disappeared, the 18th installment in the series, the governor of Wyoming has asked Joe to undertake an investigation into the disappearance of a wealthy Englishwoman who vanished after checking out of a luxury dude ranch resort. But that isn’t the only trouble Joe must face: his old friend, outlaw falconer Nate Romanowski, has asked him to look into why the federal government is interfering with falconers’ rights. And, something suspicious is going on at a nearby lumber mill where neighbors have smelled the distinct odor of incinerated hair and flesh. These cases converge as Joe Picket finds himself in a vortex of greed, corruption, violence and deadly intentions.

Mark Rubinstein: Many people consider your novels to be modern-day westerns. Will you talk about that?

C.J. Box: I consider them contemporary western novels. From the first one, Open Season, I wanted to portray the traditional western, but have it set in contemporary Wyoming. If you live in and write about Wyoming, you want to get the cultural milieu right. People still wear cowboy hats, live on ranches, and enjoy traditional activities and culture. But at the same time, Wyoming is on the cutting edge of major issues such as energy development, wind turbines, environmentalism, preservation of the wilderness and all the other social and cultural issues that go along with these areas. I incorporate them into my novels, and especially in The Disappeared. Some other portrayals of the modern west have everyone as a laid-back rube, speaking ‘kinda slow’ but that’s not the case. Other elements of the western are present in my series: a good man trying to set wrongs right, often against overwhelming odds.

Mark Rubinstein: Your novels have various thematic elements, one of them being revenge for perceived wrongs. Is this a classic western theme?

C.J. Box: I think revenge is one of the three or four classic western themes. The bad guy comes back to town and the good guy must stand up to him. You see that in a movie such as High Noon. That being said, I think revenge is a predominant theme in all of crime fiction and really, in much of literature. Think of The Count of Monte Cristo or many of Shakespeare’s plays or the ancient Greek plays where revenge plays an enormous part in the plot. There are nearly always resentments people harbor toward one another, family frictions, and feuds between warring factions. Discord may seem magnified in westerns because of the relatively sparse population.

Mark Rubinstein: Would you characterize the Joe Pickett novels as thrillers, westerns, or both?

C.J. Box: I think they’re both. I like to think of them as contemporary westerns presenting adventurous tales. As in all thrillers, there is always danger for the protagonist. But geography alone doesn’t make a novel a western. I recall talking to George Pelecanos, whose books are mostly set in the mean streets of Baltimore. He considers his books to be westerns.

Mark Rubinstein: Lee Child views his Jack Reacher novels as westerns. Will you compare them to the Joe Picket series and talk about their commonalities and differences?

C.J. Box: There are certainly similarities between the Jack Reacher books and those about Joe Pickett. Some elements of our constructions are different. Mine are wilderness-based, but in many ways, Jack Reacher is very far removed from the character of Joe Pickett.

Jack Reacher is a huge man, a wanderer and loner. He’s an unmarried former military man and is something of a mystery. He has no family roots. He seems invulnerable and is a ruthlessly efficient brawler. Joe Pickett, on the other hand, is married, has children, has a stable life and job, isn’t a brawler, and isn’t even very good with a handgun. The major similarity—and what makes Reacher and Pickett prototypal western heroes—is that both series involve a good man rooting out the bad elements in a town. They have that commonality seen in many western tales. I’m reminded of books, movies and TV shows such as Shane, Cheyenne, and Have Gun Will Travel.

Mark Rubinstein: Speaking about Joe, he isn’t a gunslinger or a dangerous and silent man like the Clint Eastwood characters. He’s a family man with likable traits. How do you account for his immense popularity?

C.J. Box: Joe Pickett is really against the grain of many crime fiction protagonists. He’s a family man, he’s employed, doesn’t make much money, he’s out on his own but he isn’t a lone-wolf type of guy. Many readers empathize with him. Women tend to enjoy the family elements of the books and many men see themselves as something like Joe—they struggle to do the right thing and sometimes, it’s difficult to achieve. That’s what I hear from readers, and that’s the kind of character I wanted to create when I started writing about Joe.

Mark Rubinstein: After writing so many Joe Pickett novels, do you face any challenges when writing about him and his family?

C.J. Box: I think the biggest challenge is keeping the writing fresh and not allowing it to become formulaic. Thus far, there are seventeen books in the series, but because they’re written in real time where Joe, his wife and children are getting older; their life experiences keep evolving, which helps the characters stay fresh for me.

I think readers are very perceptive. They can tell when an author is starting to get tired of his own material. I know as a reader, I can tell when that happens with an author. I don’t want that to ever happen with my books. I try to change things up by including topics in the news and controversial themes and subject matter in the novels. I think that keeps things fresh for both me and the reader. Life demands that we adapt, so our characters must also adapt to changing circumstances. I like that the family members grow and change with time.

Mark Rubinstein: Joe Picket has been on the mystery-thriller scene for seventeen books. How has he evolved over the years?

C.J. Box: The books take place in real time, and he gets a year older with each novel. In the first book, he was thirty-four years old and was kind of naive. Over the years, he’s been in many difficult situations and has experienced so many betrayals, he’s developed a harder bark. He’s become a bit more cynical and somewhat less trusting than he once was. The one thing that’s remained the same from the first book is that when he gets involved in a case, he’s determined to follow it through, even if it leads to bad places.

As a reader, I don’t like when a series seems frozen in time. You’ve got to suspend disbelief for a series to work in the first place, but when a character doesn’t age and change, it tips things over the top. It loses credibility. I like the fact that everyone ages a year with each book and reflects the experiences they had in the previous one.

Mark Rubinstein: In The Disappeared, there’s a very real portrayal of a contemporary dude ranch and what can happen—both good and bad things. Tell us a bit more about this element in a contemporary western crime novel.

C.J. Box: Yes, the novel focuses on many things, one of which involves very wealthy and plugged-in people—celebrities, politicians—choosing to go to dude ranches in Wyoming and the west so they can put their smart phones down for a week. A new kind of vacation has emerged where people can “live off the grid” for a while. And of course, all sorts of things—good and bad—can happen in such places. Only this morning, I saw on Twitter that Ivanka and Jared flew the Trump jet out to Wyoming, where they’re spending a week on the very dude ranch I patterned the one on in The Disappeared. [Laughter].

Mark Rubinstein: I like your comparison of westerns and crime fiction to many themes found in much of literature.

Joe Box: Thanks. I think literature through the ages often deals with the same human dilemmas: murder, revenge, greed, hubris, human frailty and frictions. That’s the case whether you write an urban thriller, a western, a domestic thriller, a detective story, a literary or spy novel.