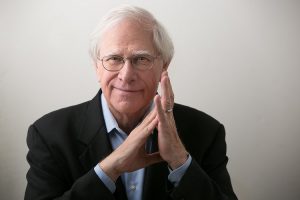

The writer John Sandford (USA) by Beowulf Sheehan, July 9, 2015, New York, New York. Photograph © Beowulf Sheehan

John Sandford is the pseudonym for the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist John Camp. After turning to fiction, he’s written many bestselling books, including twenty-seven Prey novels, his most recent being the just-released Golden Prey. He’s also penned four Kidd novels; nine Virgil Flowers novels; three standalone novels, and three YA novels coauthored with his wife, Michele Cook.

Golden Prey sends Lucas Davenport on a sustained manhunt for Garvin Poole who’s been lying low for years. It’s been rumored he’s dead; but Poole resurfaces in Biloxi, Mississippi where he has masterminded a heist of millions of dollars from a Honduran drug cartel. The operation has left five people dead, including a six-year-old girl. Poole unwittingly left behind some of his DNA, so the authorities know he’s alive and back in the game.

When Lucas, now a U.S. marshal, and his team begin tracking Poole, complications arise as the Honduran cartel has sent its own killers to track Poole, reclaim the money, and exact retribution.

Lucas Davenport is a larger-than-life character. Will you give us a brief description of him?

He’s tall and good-looking in a rugged way. He has a couple of scars on his face and one on his neck, and he’s got a mean smile, but kindly eyes. He likes excitement and intensity, and doesn’t shy away from a fight. When I put him together, I tried constructing a character both men and women would like. He’s a tough guy but really likes smart women. He has a great fashion sense, and wears clothes well.

There are two fascinating villains in Golden Prey: Garvin Poole and Sturgill Darling. Despite their criminality, they’re complex characters with deep commitments to women, and to each other. Will you talk about villains and what makes them interesting?

Many things can make a villain interesting. You know, a typical killer so often described in thrillers is despicable from start to finish: his nose drips, he’s pure evil. These two guys are country people who are out of time. They don’t live in the computer world, even though they have computers. In his spare time, Garvin Poole makes electric guitars. He’s not the kind of guy who’s going to make it in an office or working a nine-to-five job, he’s independent to his core.

Sturgill Darling is a serious farmer, who maintains a well-tended farm and he’s committed to his wife.

I like them both even though they’re bad guys. They’re likable because they were shaped to some extent by forces they couldn’t control—each had a deprived past. I think the most appealing villains are those who act badly but aren’t bad human beings. Interesting villains have more than one dimension and have different facets to their personalities.

Golden Prey features a great deal about technology in tracing and tracking criminals. How have you kept up with these modern techniques?

One thing I realized when I began the book is that it’s impossible to write an old-fashioned crime story like those featured in the sixties and seventies. It doesn’t work well anymore. Those people left clues that can no longer be contested in court. Take DNA for example, it’s impossible to refute if it’s found.

If you write contemporary police procedural novels, it’s tough for anyone to get away with anything.

Consider the iPhone: it tracks every place you’ve been. That means the cops can accurately place you at the crime scene; and it’s the same thing with the GPS navigation system in your car.

For me, technology is almost a character in the book, albeit a very complicated and omnipresent one. Yes, I do research but I’m also struck by how people are so consumed by it and connected to it. You can’t walk down the street without encountering many people on their cellphones texting or talking.

Who do you find more compelling to write about: Virgil Flowers or Lucas Davenport?

I don’t find either one more compelling than the other because they’re totally different from each other. Virgil is a guy who is sort of left in the past. The killings he gets involved with are more mundane than those in which Lucas is involved. The perpetrators are usually the losers in society. They’re not clever criminals. Virgil allows me to use my sense of humor much more than Lucas does.

Lucas Davenport is much more intense and far darker than Virgil Flowers. I like writing both of them. Virgil is very much of a release for me after writing about Davenport because I can have fun with him as opposed to the intensity of Davenport.

Is there anything about your writing process that might surprise our readers?

I don’t think there’s anything about the process itself that might surprise readers; however, perhaps they don’t realize it’s very hard work. I’m sitting at a computer many hours every day. Because the work is so consuming, I have to make an effort to get away from the novels. I have to force myself to take a break to exercise. I didn’t exercise yesterday; I sat at the computer for most of the day, and as a result, today I have a sore back. Writing is actually very hard work. I don’t just type a few words and then go out for a latte. [Laughter]. I know people appreciate when the book is good, but I think they don’t understand how hard it is physically and mentally to write.

When we last talked, you mentioned wanting to “cut back” to one novel a year so you could pursue other interests. But you’re still writing at a torrid pace. Tell us about that.

I’m going to have to cut back sooner or later because the pace really does hurt, and it keeps me from doing other things. I sit at the computer for hours every day, but, even when I’m not actually writing, I’m thinking and talking about it. For instance, last night my wife and I sat down and had a protracted conversation about the possibility of writing two other novels. We discussed all the complications of establishing the plots. When I’m doing two books a year, even when I’m away from the computer, I can’t get away from the writing.

For instance, when I walk around on the street, I look at signs, trucks, and bumper stickers, all of which contribute ideas for the books. Even when I’m in the car just out for a cruise, I’ll see something interesting and make a mental note of it. And it all comes down to the fact that I can’t get away from the writing and find it very hard to relax.

I’d like to be able to pursue other interests, like play a round of golf which I used to enjoy, but writing demands a great deal of my time and soaks up my physical and mental energy.

When you write a YA novel with your wife, how do you switch gears for a very different audience?

That was hard, too. But, I have youngsters in the Davenport books and also in the Virgil Flowers books. The kids in the YA novels and those in Virgil’s are sort of old-fashioned kids. They’re not the type of kids walking down the street with friends where all of them are on their cellphones. They’re from a somewhat earlier era. They’re not sexting on their cellphones. In a way, they’re not truly modern kids. I simply can’t conceive of some of the things kids do today.

I understand you once wrote a non-fiction book about plastic surgery. Will you tell us about that?

I wrote two non-fiction books: one about art, and the other about plastic surgery. When I was a reporter, I became interested in medical reporting. I wrote a few stories out of a hospital emergency room. I became very interested in medical and surgical issues. Then, I saw some patients who’d been severely burned and became aware of the emotional impact burns had on patients. I saw plastic surgery performed on a little girl who’d had all the hair on her head burned off in a mobile home fire. She had terrible scarring on her scalp. I watched a plastic surgeon do reconstructive surgery on this child and he restored all her hair. I interviewed the surgeon, who convinced me that appearance is a critical issue for people. I asked him if we could put together a book detailing a whole series of plastic surgical cases. I compiled a few dozen cases and incorporated them into the book. Some were reconstructive while others were for aesthetic reasons, but all were vitally important for the patients.

What’s coming next from John Sandford?

I’m almost two-thirds of the way through the next Virgil Flowers book.

Congratulations on writing Golden Prey, a blistering addition to the Prey series. The books are so compelling, Stephen King said, ‘If you haven’t read Sandford yet, you have been missing one of the great summer-read novelists of all time.’