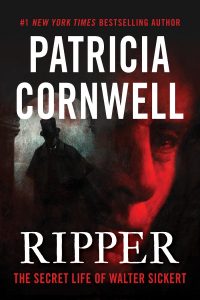

Patricia Cornwell is known to millions of readers as the award-winning and bestselling author of the Kay Scarpetta series. In 2001, she was pulled into a real-life investigation of her own—the long-unsolved “Jack the Ripper” murders that appalled and fascinated London in the late 1800s. Applying old-fashioned as well as modern forensic techniques to a century old crime, Patricia Cornwell’s research led to the publication of Portrait of a Killer, in which she identified the renowned British painter Walter Sickert as the Ripper.

Patricia Cornwell is known to millions of readers as the award-winning and bestselling author of the Kay Scarpetta series. In 2001, she was pulled into a real-life investigation of her own—the long-unsolved “Jack the Ripper” murders that appalled and fascinated London in the late 1800s. Applying old-fashioned as well as modern forensic techniques to a century old crime, Patricia Cornwell’s research led to the publication of Portrait of a Killer, in which she identified the renowned British painter Walter Sickert as the Ripper.

The book created considerable controversy and thereafter, Patricia devoted countless hours and resources pursuing new evidence against Sickert. In Ripper, The Secret Life of Walter Sickert, she revisits, revises and expands upon her findings of the most notorious unsolved crime wave in history.

Give us a brief overview of Jack the Ripper’s crimes and the impact he had on London in the 1880s.

Jack the Ripper’s crimes began then, but there was nothing in the London newspapers about a “Jack the Ripper.” The first reports noted some fiendish killer was terrorizing the impoverished East End, an area of slums known as Whitechapel. A prostitute was killed at the end of August of 1888; she’d been stabbed more than twenty times. Nobody paid much attention to it. Then, another woman was murdered soon afterwards; her throat was cut in the streets of the East End, in the early hours of the morning.

The murders became infamous when “Jack the Ripper” began writing letters to the media and to the police. He named himself “Jack the Ripper” and signed the letters using that name or others such as “Saucy Jack” or “Jackie Boy.” The letters were hateful, violent and mocking. By the end of September of 1888, there were five, if not six, murders attributed to Jack the Ripper. In the London slums where the prostitutes and immigrants lived in a sea of misery, they talked about “The Knife” and warned each other to be aware there was someone out there who killed.

the Ripper” and signed the letters using that name or others such as “Saucy Jack” or “Jackie Boy.” The letters were hateful, violent and mocking. By the end of September of 1888, there were five, if not six, murders attributed to Jack the Ripper. In the London slums where the prostitutes and immigrants lived in a sea of misery, they talked about “The Knife” and warned each other to be aware there was someone out there who killed.

Then the worst murder occurred which was the killing of Mary Kelly in early November of 1888. She was not murdered in the streets, but in her hovel. All her organs were removed but her brain, and she was flayed to the bone. Her right leg was flayed down to the femur.

We don’t know how many murders Jack the Ripper actually committed. There’s a great deal of evidence that there were at least seven, and probably many more as I point out in the book. These kinds of killers change how they commit murder. The stakes escalate for such a killer. From a psychological standpoint, it takes more to satisfy the compulsion to kill. I believe that’s when Jack the Ripper began to dismember his victims.

What made you so interested in solving these crimes?

It’s what happens to me with anything that gets my attention.

In the Spring of 2001, a Scotland Yard investigator gave me a tour of the Metro Police headquarters, and took me to the East End where these murders had occurred. I was simply being given a tour. I then asked a fateful question: ‘Who were the suspects?’ He rattled off the names, many of which were familiar to Ripperologists. He said they were suspects with no basis in fact or evidence. It was just speculation. I asked about any evidence and he told me the only evidence left in the case were the actual letters the Ripper wrote to the media and police. They were in the national archives. I considered the fact that documents can provide a plethora of forensic evidence.

There can be DNA evidence or even statement analysis, which can be a valuable tool in an investigation—the perpetrator’s choice of words, his language, the spellings and misspellings—can be revealing.

I decided to look at the letters.

The investigator told me an artist had been named as a possible suspect in the Ripper case: one Walter Sickert, a prominent English artist during the Victorian era.

I began looking at art books and the hair on the back of my neck stood up: Sickert’s paintings were very disturbing. They conveyed an undercurrent of morbidity and violence, particularly against women. But that wasn’t enough to make me think Sickert had committed the crimes.

I looked at the archived letters and was shocked. Readers will see in both the e-book and print edition of Ripper these paintings and letters. You can see how the watermarks match, and how the paintbrush strokes where he painted a letter instead of writing it conform to each other. The art work itself presents a compelling and multi-layered and very clear case against Walter Sickert.

As the book notes, Walter Sickert was a well-known painter and student of James Abbott Whistler. Tell us a bit more.

The most amazing thing about the Ripper case is that nobody ever imagined that Jack the Ripper was part of the Victorian art world—the theatrical stage and the art studio. Sickert started out as an actor. Interestingly, his stage name was ‘Mr. Nemo’ which means Mr. Nobody. One of the telegrams Jack the Ripper sent was signed ‘Mr. Nobody,’ then it was crossed out and replaced with ‘Jack the Ripper.’

Jack the Ripper wrote letters he signed ‘Nemo.’ He wrote many letters to the editor of a newspaper. This perpetrator had graphomania; he was a compulsive writer. Sickert was also a compulsive writer. He would apologize to friends for writing so often. He had a psychological compulsion to murder. It was an addiction that took the place of sex and other normal things people seek for gratification.

Speaking of psychology, in Ripper you compare Walter Sickert’s compulsion to murder, likening him to Robert Louis Stevenson’s novella, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Will you talk about that?

This all sprang forth from the London stage.

Sickert went from being a failed actor to becoming an apprentice of James McNeill Whistler, the painter of ‘Whistler’s Mother.’ Whistler was flamboyant and famous for running around the streets of London with Oscar Wilde. He was like a modern-day rock star. Sickert felt diminished around this famous man, which added to his feelings of belittlement and rage. This tapped into his sexual inadequacies concerning a deformity of his genitalia, as detailed in the book. Sickert had three surgeries for a fistula on his southern hemisphere by the time he was five years old. He underwent these surgeries without anesthesia which left him physically and emotionally scarred for life.

In the summer of 1888, A famous American actor, Richard Mansfield, wanted to bring Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to the London stage. Mansfield mounted the production in August of 1888. Sickert knew all about this because he was an actor in that same theater, and in fact, the stage manager was none other than Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula. They all knew each other.

The theme of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde concerns a duality of someone who, on the surface is respectable, but who transforms into a monster. It’s a metaphor for the psychiatric pathology of a compulsive killer. It’s a picture of the two faces of this type of person. I once asked an expert who had dealt with sexual psychopaths—people like Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer—when do we know when someone who is charming and attractive is truly evil, and a killer? He said, ‘You know it about one minute before they kill you.’

This book shows people what this kind of killer really is like. It speaks to the need to get away from mythologizing him.

Jack the Ripper was not a charming top-hatted man in the London fog. He was a monster in the fog, with whom you might have coffee in the morning and think he’s witty, nice-looking, but a bit cold, not empathic, and who never feels guilt or regret about anything.

Tell us about the modern forensic techniques you brought to this investigation.

My investigation was an alchemy of the lowest and highest forms of technology imaginable. I used both in this case. I put letters on an old-fashioned light box or under a microscope. I even used a magnifying lens to examine the paper on which the Ripper wrote. I brought in experts to examine the paper which involved taking precise measurements of the hand-made paper and studying its watermarks. It became like fingerprints in the case.

As for the latest technology, we used spectroscopy and DNA analysis—non-destructive techniques to learn more about these hundreds of letters. Because they’re considered national treasures, we couldn’t take these letters to a laboratory and run forensic tests because they cannot leave the archives or risk being damaged. I brought over a Harvard scientist to look at colored pencils, lithography instruments, etching materials, and paint brushes. In one of the letters, Ripper penciled the letters first and when looking at it under a lens, you can see he dipped a paint brush in red ink and painted the letter. That wasn’t done by some deranged miscreant living in the London slums.

Congratulations on writing Ripper: The Secret Life of Walter Sickert. It’s a highly readable expose of perhaps the world’s most famously chilling case of serial murder; the vain efforts of the police to solve the crimes; and the compelling revelations your exhaustive research has unearthed.

Mark Rubinstein’s latest book is Bedlam’s Door: True Tales of Madness and Hope, a medical/psychiatric memoir.