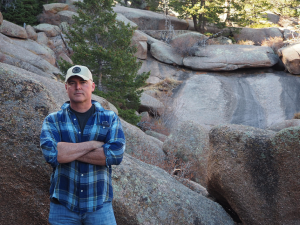

Steve Hamilton has either won or been nominated for virtually every major crime fiction award, including the Edgar, Dagger, Shamus, Anthony, Barry, and Gumshoe, among others. His Alex McKnight series involves ten bestselling and highly acclaimed books. His standalones include Night Work, and The Lock Artist which won the Edgar and Barry Awards for best novel of 2011.

Steve Hamilton has either won or been nominated for virtually every major crime fiction award, including the Edgar, Dagger, Shamus, Anthony, Barry, and Gumshoe, among others. His Alex McKnight series involves ten bestselling and highly acclaimed books. His standalones include Night Work, and The Lock Artist which won the Edgar and Barry Awards for best novel of 2011.

The Second Life of Nick Mason was Steve’s first entry in a new series. Nick Mason is an ex-con, trying to break away from his criminal past. Because of an arrangement with Darius Cole, a Chicago crime lord, he’s been released early from prison. But because of that favor, Nick finds himself forced to commit increasingly more dangerous crimes while being pursued by the detective responsible for putting him behind bars.

Exit Strategy, the second in the Nick Mason series, finds Nick assigned to ever more dangerous missions: he must infiltrate the U.S. Federal Witness Protection Program and kill the three men responsible for Darius Cole’s life-sentence conviction. But Nick is being hunted by the very man he replaced, a ruthless assassin who once served Darius Cole.

The first lines of Exit Strategy are: “You kill one person, it changes you. You kill five…it’s not about changing anymore. It’s who you are.” Talk about the importance of the opening lines of a thriller novel.

It’s sort of like the first few notes in a rock song. it puts you there right away. Those opening lines set the tone for everything that happens afterwards. And, it serves as a hook for the reader. It sets up the whole scenario about Nick Mason.

Speaking of Nick Mason’s scenario, he’s something of an anti-hero. What do you feel makes him so appealing?

I’ve been a bit overwhelmed by how well he’s been received. He’s not someone I would ever have tried to write about when I was starting out.

He’s not Alex McKnight, that’s for sure.

Absolutely. Alex, who spent his life on the right side of the law, is now getting reluctantly dragged into things. A few years back, I wrote a book about a young safecracker—The Lock Artist—which was a departure for me.

Nick Mason is even a bigger departure. He’s a career criminal, and he’s in prison—not because he was wrongly accused—but because he made a huge mistake. As a writer, I found him to be a bit of a challenge to depict convincingly. I wondered if I could make the reader root for him.

I found the dynamic of his wanting to get out of prison to see his family to be very compelling. If he could make amends for his mistake, the reader would come to like and relate to him. But the circumstances he finds himself in—having to answer to Darius Cole and do whatever he’s told to do, no matter what it is—are horrifying. It’s turned into such a pressure cooker for him, and he’s just trying to survive.

True, he’s living in a nice townhouse and has a car and money provided by Darius Cole, but on the other hand, his life’s a total nightmare. No matter which way he turns, he’s between Scylla and Charybdis.

There’s a surprising twist at the end of Exit Strategy. Tell us about the role of twists in thrillers.

Twists are what it’s all about. There’s almost a bit of cruelty in my writing this kind of twist into Nick’s life.

Be it a thriller or a literary work, the role of the twist is to knock the protagonist off-balance, and the reader as well. I know I love reading a novel that throws me an unexpected curve ball.

It’s like life itself.

Yes, it is. [Laughter]. How many of us could have imagined we’d be exactly where we are at this moment?

Nick Mason is a very different character from Alex McKnight, your first series protagonist. Talk to us about character development in your novels.

He’s different from Alex McKnight, yet, they actually have things in common. They’re both very loyal people and are dedicated to what they do. Mason was very careful about what he did as a criminal and does his best to live by a certain code, as does Alex McKnight. I think they’re sort of mirror images of each other.

If you recall the diner scene in the movie Heat, Robert Di Niro and Al Pacino sit across the table from each other and realize they’ve got a lot more in common than they thought.

When I create any character, I’m looking for a fully-realized person in every way. Even if I’m writing a villain like Darius Cole, I try to construct understandable reasons for what he does.

People are multi-faceted with reasons behind their actions and I do my best to portray that in my novels.

You wrote your first twelve books—some of which were bestsellers—while working for IBM, writing at night after your family had gone to bed. Tell us about your path to success.

I always wanted to be a writer. After graduating from college and working for IBM, I knew I wanted to keep that promise to myself. For a long time, I was living a double life: working during the day and writing at night. A lot of people do that—even some very successful authors. John Grisham was working as a lawyer, and Raymond Chandler was an oil company executive.

I think it’s what you have to do to make that dream come true. I was very fortunate that after a number of years, it really did happen for me.

You have an idea for a novel, be it about Nick Mason, Alex McKnight or a standalone book. What’s it like when you first sit down to write that novel? Do you have butterflies, or feel nervous?

[Laugher] Yes, it’s terrifying trying to create something out of nothing—staring at an empty page or a blank computer screen. Even now, it doesn’t get any easier, and I don’t think it should.

If it ever gets too easy, I’m probably not doing my best work. I think every new book should be scary.

Has your process of shaping novels changed since writing that first one? How do you go from the initial idea for a novel to the finished manuscript?

It’s different now. With most of the Alex McKnight books, I was learning how to write a crime novel, and how to write a series. I never really knew where I was going to end up with a story. It may seem like a romantic way to write a novel, but as I kept doing it, I found establishing the structure of the story produced a better result for me.

By the time I wrote the first Nick Mason novel, I knew where I was going. I wasn’t getting lost in the plotline. I could still surprise the reader without being surprised myself. When I wrote The Second Life of Nick Mason, I already had seven future novels laid out in my mind.

What’s your writing day like?

Every writer has a different method of writing novels. I know many writers get up at dawn and write. That always surprises me because I’m something of a night owl. I do my best work after dark. Maybe it’s just a continuation of when I was still working at a day job and wrote at night.

I know you have a few people you’ve used as your first readers. What role do they play in producing the book that goes to print?

Years ago when I joined a writers’ group, I promised myself I’d find a few people whose judgment and opinions I could trust to improve my manuscripts.

Bill and Frank were two guys I’d see every week when I was writing the McKnight books. They helped me tremendously.

Now, I work with Shane Salerno, my agent. He helps keep me on track. An important part of being a writer is listening to someone you can trust—someone who will tell you if you’re going off the rails or if you’re headed in the right direction. Shane does that for me.

You’ve written both standalone novels and series. What differences and difficulties do you find in these approaches?

When I write a series, it feels like each book is one piece of a larger landscape. One book leads into another. There’s an expansive arc to the entire story, encompassed by the series itself.

In a standalone, I’m trying to tell a compelling story within one volume. In a way, I’m trying to encompass an entire life in one book.

How far along the process is Lionsgate in bringing Nick Mason to life on the big screen?

It’s in development. They’re still on track with it and there’s going to be a big announcement in the next few days.

Who do you see playing Nick Mason?

I guess I wish it could be a young Steve McQueen. He was someone who had the qualities that could make you want to root for the character. But now, since that’s not possible, I’m glad someone with casting expertise will be making that call.

What’s coming next from Steve Hamilton?

I’m working on the next Nick Mason book and have already turned in the next Alex McKnight book.

Congratulations on writing Exit Strategy, a compelling trek across very dark terrain putting Nick Mason through increasingly pulse-pounding paces with so much non-stop suspense, I read the book in two sittings.

Dr. Rubinstein shows, once again, the humanity of the people who live with a variety of mental health illnesses. He shows their vulnerability to those wholack the compassion of “do not harm.” He reminds us that respect is a major aspect of how to support and help these patients. By recounting these 21 stories, the author shows us that:

Dr. Rubinstein shows, once again, the humanity of the people who live with a variety of mental health illnesses. He shows their vulnerability to those wholack the compassion of “do not harm.” He reminds us that respect is a major aspect of how to support and help these patients. By recounting these 21 stories, the author shows us that: