Adrian McKinty’s life story is extraordinary. He grew up in Belfast, Northern Ireland during the “Troubles.” After studying law, he attended Oxford University on a full scholarship to study philosophy and politics. While writing on the side, he worked at many occupations in the UK and U.S.: security guard, bartender, truck driver, bookstore clerk, rugby coach, door-to-door salesman, high school English teacher, and librarian.

Adrian McKinty’s life story is extraordinary. He grew up in Belfast, Northern Ireland during the “Troubles.” After studying law, he attended Oxford University on a full scholarship to study philosophy and politics. While writing on the side, he worked at many occupations in the UK and U.S.: security guard, bartender, truck driver, bookstore clerk, rugby coach, door-to-door salesman, high school English teacher, and librarian.

As a full-time novelist, he’s either won or been nominated for nearly every thriller or crime novel award in existence.

His latest novel, The Chain, is a mesmerizing excursion into a chilling crime that challenges the protagonist and reader in unimaginable ways.

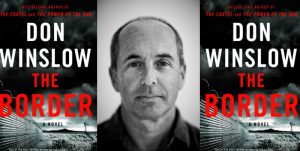

Mark Rubinstein: Stephen King called The Chain “Nightmarish and propulsive,” while Don Winslow said “This book is Jaws for parents.” Describe to us the opening premise of The Chain.

Adrian McKinty: The Chain is the story of Rachel O’Neill, who gets a call from a stranger telling her that her 11-year-old daughter has been kidnapped. She also receives a photograph of her daughter. Rachel asks, “Why are you doing this?” The caller says, “Because my child has been kidnapped by a stranger. I must pay the ransom and replace my child on the chain with another child whom I’ve kidnapped. And you must do the same thing. You must pay the ransom and replace your child on the chain with someone else. If you break any of the rules or go to the police, I will kill your child and pick someone else.”

In this universe, Rachel is first a victim; becomes a co-conspirator; and then must become a kidnapper. So her entire moral universe collapses in a matter of days.

Mark Rubinstein: How did the idea of a chain kidnapping come to you?

Adrian McKinty: It brewed in my brain for years. When I was in Mexico City, I came across an article about kidnappings in Mexico. It’s an organized business where loved ones are kidnapped and held for ransom. What struck me was an arrangement whereby someone receiving a ransom demand could swap places with the kidnapped family member, while the rest of the family raised money. This business angle and the notion of swapping kidnapped victims made a deep impression on me.

Another element is when I was a kid growing up in Ireland, chain letters went around saying unless you joined a chain, a dreadful curse would befall you. We youngsters were very superstitious and scared of these things. I really believed this stuff. One day, a teacher of ours demanded that we bring the chain letters to her; she made a big bonfire and destroyed them. She broke the chain. I know she lived a long and happy life. I’ve always remembered her over the decades.

The third element was the Greek myth of Demeter and Persephone. Demeter saved her daughter from the abyss and brought her back from Hades; but not all the way, which is why the Greeks believed winter was followed by spring and regrowth.

These three elements coalesced into the story of The Chain.

Mark Rubinstein: In The Chain, Rachel O’Neill is challenged by circumstances far beyond the realm of any ordinary life. Why do you think such horrific events play so powerful a role in crime novels, and talk about their effects on even the most law-abiding people?

Adrian McKinty: I’ve thought about this a great deal. When I studied philosophy, I read Aristotle’s thoughts about ethics and morality. He believed actions define who you are. Virtue is decided by what you do. I loved this concept as defined by Aristotle. I wondered about taking a good person who’s been challenged by life (Rachel is a cancer survivor) and testing her beyond endurance. What if I made her do terrible things? If she becomes a bad moral agent, does she become a bad person? I wanted to take the reader on that philosophical journey. There’s really no unequivocal right answer to that question. I think that instinctually, the reader realizes that Rachel does what we ourselves would probably do.

Mark Rubinstein: What are your thoughts about the profound hold kidnappings have had on the readers of crime and suspense/thriller novels?

Adrian McKinty: It’s interesting because there are very few ransom kidnappings in America. The FBI reports fewer than one-hundred ransom kidnappings per year occur in the United States. About ninety-five percent of kidnappings are carried out by estranged parents in custody disputes. Stranger kidnappings for ransom—those that dominate crime novels and movies—are very rare. But they involve a singular terror: your loved one has been kidnapped by a stranger whose motive is money. If the money isn’t paid, this stranger will harm or kill your loved one. That situation generates profound terror.

Mark Rubinstein: Your own odyssey through the literary landscape has been quite unusual. Will you tell us about it?

Adrian McKinty: I studied philosophy but realized there was no practical way to earn a living with that background. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. I met a girl from New York. We got married and I moved to New York, got a job in a bar and did some other things.

When we moved to Denver, Colorado, I became an English teacher. I had the kids write short stories. This went on for a few years and finally, the kids demanded that I write a story. So, I began an autobiographical story. It got longer and longer until it was novel length. I read a bit of it to the kids who liked it. I sent it off to a publisher where it was rejected; but a second publisher accepted it. I became a published author in the early 2000s. That was the beginning of my odyssey into crime fiction.

Mark Rubinstein: I understand that while you had a number of books published and won awards, you weren’t financially successful until recent developments.

I had been teaching and writing was a hobby. Then, my wife was offered a job in Australia. After our move, I decided to write full-time and that’s where things began going wrong. My American and British publishers decided to drop me. I found a new publisher in England and wrote a series of crime novels about a detective named Sean Duffy. They received fine reviews and won awards, but sales were dismal. Simply put, for four or five years, I wasn’t earning a living. I was broke and eventually, we were evicted from our house.

Despite acclaim for my writing, I was doing nothing for my family. So, I decided to stop writing. and get a proper job. I posted my decision to stop writing on my blog. I got a job at a bar and became an Uber driver.

Then, of all things, I received a telephone call from Don Winslow, one of my idols. He’d read my blog and asked why I was quitting writing. I couldn’t believe it! He asked if I would mind him giving a few of my books to a friend of his, Shane Salerno. I said that would be fine.

A few weeks later, I got a phone call after midnight. It was Shane Salerno, an agent and screenwriter. He said books about a Belfast detective were a hard sell in America. He encouraged me to write an American story. I said I’d made my decision and was going to hang up the phone, which I did. It rang again and I hung up on him a second time. The phone rang a third time; and you know what the Talmud says about three times…

During this third call, Shane said I was being woefully represented by my agent and the publisher. He asked me to pitch an American story to him.

Those three elements we talked about earlier came to mind.

I told him about an idea I’d had for a short story, but hadn’t written. It was called The Chain. I pitched it to him. He said, “I want you to write this book, right now.”

At 2:35 in the morning, I found myself in front of a blank computer screen, writing the first 30 pages of the story. It just flowed. I sent it off to him. A while later, the phone rang. It was Shane. He said, “We need three-hundred more pages like this.” And that’s how I ended up writing The Chain.

Mark Rubinstein: And Paramount will be making a major motion picture of The Chain. So, the moral of the story is?

Adrian McKinty: I got lucky. I’d given up. Many successful writers, like Don Winslow, are generous and supportive people. For quite some time, Don had a great deal of critical acclaim but poor sales. If not for Don, and then Shane, I might still be driving an Uber or tending bar. I think the moral is to stay connected to the writing world, and above all, never give up.