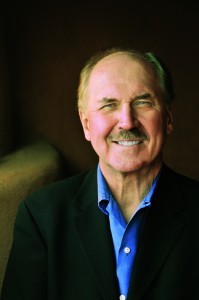

David Morrell is an acknowledged master of the suspense/thriller genre of storytelling. His iconic protagonist of First Blood, John Rambo, is one of the most enduring figures in contemporary fiction. As a professor of American literature at the University of Iowa, Morrell both taught and wrote novels until he eventually resigned his professorship to write on a full-time basis.

He has either won or been nominated for virtually every award in the suspense/thriller universe and has authored twenty-eight novels, along with having written short fiction, a graphic novel, and non-fiction books.

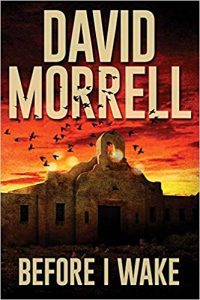

Before I Wake is his third short-story collection comprised of fourteen stories showing his talent for transcending any one genre.

Mark Rubinstein: David, the first story in this collection, “Time Was,” was especially eerie. You called it “an example of my Twilight Zone-type stories” and you mentioned Rod Serling as an early influence. How did the idea of this story come to you and tell us how Rod Serling influenced you?

David Morrell: When I was young, my mother insisted I have a job every summer. One summer, I worked as a construction worker. I was terrible at it and was fired within a week. I went ho me and turned on the TV to a movie called Patterns, which was written by Rod Serling. I learned soon afterwards that Serling was not only a Playhouse 90 writer, but also created The Twilight Zone. I got immersed in that world and devoured Ray Bradbury stories, too. For years, my short stories tended to be in the Serling-Bradbury mold. I received three Stoker Awards from the Horror Writers Association and two finalist nominations. I often come back to writing horror stories conveying eeriness where the nature of reality is questioned. I think the gene is in my DNA.

me and turned on the TV to a movie called Patterns, which was written by Rod Serling. I learned soon afterwards that Serling was not only a Playhouse 90 writer, but also created The Twilight Zone. I got immersed in that world and devoured Ray Bradbury stories, too. For years, my short stories tended to be in the Serling-Bradbury mold. I received three Stoker Awards from the Horror Writers Association and two finalist nominations. I often come back to writing horror stories conveying eeriness where the nature of reality is questioned. I think the gene is in my DNA.

Mark Rubinstein: The second story in this collection, The Architecture of Snow, pays homage to J. D. Salinger who intrigued you. What about Salinger drew you to his life and story?

David Morrell: I was fascinated by the fact that at the height of his fame, Salinger became a recluse. In 2004, I became shockingly aware of what was happening in publishing: publishers’ marketing departments had dominance over editorial departments. Editors would consider buying something, but the marketing departments would tell them whether or not the book would sell. They made decisions on that basis. I realized the publishing business had changed.

From this situation, I got the idea of a reclusive writer, someone like Salinger, who, late in his life, sent a manuscript to his editor (who was also a friend). But, he used a pseudonym. He wanted to prove that a good book would sell without his name being on it. However, the original editor died. So, what would the publisher do with his manuscript?

I wrote the story in the first person and made the reader a character in the story. It’s an eerie tale, and in essence, is a’ Please buy my book’ story.

Mark Rubinstein: Within the pages of Before I Wake, you mention your fascination with orphans, foster fathers, and trying fill a void for a lost loved-one. Those themes are also explored in your novels Desperate Measures and Long Lost. Your memoir, Fireflies: A Father’s Tale of Love and Loss, plumbs those depths. Will you share the journey that led you to these themes?

David Morrell: It starts with the fact that my father was killed in combat in World War II. I never knew him. My mother tried to support me and work as a seamstress, but she couldn’t do both. When I was three years old, she reluctantly arranged for me to be placed in an orphanage. I tried to escape a couple of times. The experience has remained a vi vid memory throughout my life.

vid memory throughout my life.

My mother remarried, but my stepfather didn’t like children. They fought a great deal and there were times when I sought refuge beneath my bed, and told myself stories about rescuing people. In a way, I became a self-predicted thriller writer.

So, at a young age, I was conditioned to believe that life can change quickly, and for the worse. I’ve always felt if you can get through a day without a disaster happening, it’s a lucky day. The reigning theme in my work is ‘don’t be surprised when bad stuff happens. You must be prepared for crises.’

Compounding this was the fact that my 15 year old son, Matthew, died from a rare bone cancer. And, some years later, my granddaughter died from the same disease at 14 years of age.

I’ve had a successful career and a wonderful marriage, yet these tragedies happened to me. So, the theme of my work is one of preparedness so as not to be taken by surprise by disaster. That’s why I write about spies, police officers, and protective agents because anything can happen to them at any moment. I’m interested in the psychology of these people who can move forward without being psychologically destroyed.

Mark Rubinstein: The various stories in Before I Wake defy being assigned to any one genre. You write thriller stories, tales of espionage, some with an eerie sci-fi flavor, and a Victorian tale about Thomas De Quincey, “The Opium Eater.” How would you define yourself as a writer, and what do you think of today’s tendency to assign genres to authors?

David Morrell: I stared writing fiction at a time when genre writing didn’t dominate the bestseller list. How I spend my time writing is of the utmost importance to me. I will not write a book that doesn’t have value in terms of the prose, the theme or its research. The book must sustain my interest to account for the time I devote to writing it.

Over the years, I’ve migrated from action stories in the 70s, to espionage in the 80s, then to more artistic thrillers in the 90s. This decade has involved my writing historical thrillers. It’s all based upon what interests me. Fortunately, I’ve had a core of faithful readers who’ve stayed with me no matter which genre I’ve written. I think my career has lasted so long because I’ve been willing to explore different areas that have interested me. Today, genre branding is the norm, which I don’t think is healthy.

Where did the title Before I Wake come from and what does it mean?

David Morrell: I have two prior collections of short stories: the first is Black Evening and the second, Nightscape. I thought I’d unify the titles. So, Before I Wake seemed quite appropriate as a nightmarish metaphor.

Mark Rubinstein: Last question, David. What would you say if today you were to meet the young David Morrell, a professor of American literature, who was interested in becoming a novelist?

David Morrell: My standard advice when talking to young writers is twofold: ‘Be a first rate version of yourself and not a second rate version of another writer’ and ‘Don’t chase the market because you’ll always be chasing its backside.’

In today’s publishing world, trends are more than ever ruling the marketplace.

But if you start putting ‘Girl’ in the title, or write the same kind of book again and again, you’re typed as not being original.

Philip Klass, my writing instructor from years ago, insisted that writers who went the distance and enjoyed long careers, were those who had a definable viewpoint and a unique personality in their prose. That’s been my lifelong goal as a writer.