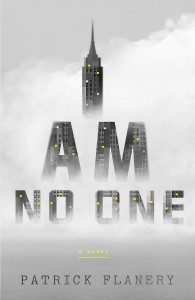

Patrick Flanery earned a B.F.A. in film at NYU and worked in the film industry before moving to the U.K, where he completed a doctorate in Twentieth-Century English Literature at Oxford. He has written for the Washington Post and the Times Literary Supplement, and is a professor of Creative Writing at the University of Reading. I Am No One is his third novel.

I Am No One features Jeremy O’Keefe, a divorced, middle-aged history and film lecturer at NYU, who has returned from the U.K. after spending a decade teaching at Oxford. He had left New York, his crumbling marriage, and young daughter after not receiving tenure at Columbia. Now back in the city, he begins to receive a series of mysterious packages, each one containing seemingly incontrovertible evidence that every aspect of his digital life over the last ten years has been the subject of intense surveillance. At the same time, he repeatedly encounters a strange young man who appears to know exactly where Jeremy is going or has just been.

And who’s that darkly clothed figure Jeremy sees on so many nights peering at his apartment windows?

What is going on …. and why?

The reader is drawn into Jeremy’s world of possible paranoia and delusion; or is it one of a frightening level of all-encompassing surveillance?

On one level, I Am No One deals with the issue of surveillance, either by the state or by rogue players. Will you talk about that?

When I started writing the book, I didn’t set out to write a novel about surveillance. I was thinking about a moment I’d experienced in New York City. I was staying with a friend who was living in Silver Towers. I was on the street and looked up at her bedroom window. I waved to her, but she didn’t see me. I told her I’d seen her and it was the first time she’d been aware she was living a half-public life in her own apartment. That made me think of crafting a story about different kinds of intrusions into one’s private life. It made me want to explore the kind of characters who would be at the nexus of that experience. That led to a broader story about surveillance. It became a book about different kinds of watching and the experience of being watched—both on a personal level and in a larger, more abstract governmental way.

You can probably discuss this extensively: Is I Am No One a political thriller, a cautionary warning, an existential meditation of self and the world, or a combination of all three?

I think it can certainly be read with all three of those categories in mi nd. In some ways, the novel is trying to engage the possibility of each of those genres. The book is conscious of its status as something involving complexity. There are moments when Jeremy wonders what kind of novel he’s in. Is he in a thriller, a drama? It’s also a novel about how we live our lives these days and how we think about ourselves. People interested in a political thriller will find something identifiable for themselves. However, it’s not a novel that plays by the rules of commercial thrillers.

nd. In some ways, the novel is trying to engage the possibility of each of those genres. The book is conscious of its status as something involving complexity. There are moments when Jeremy wonders what kind of novel he’s in. Is he in a thriller, a drama? It’s also a novel about how we live our lives these days and how we think about ourselves. People interested in a political thriller will find something identifiable for themselves. However, it’s not a novel that plays by the rules of commercial thrillers.

All your novels deal, at least partly, with contemporary political and social issues. Will you talk about that?

[Laughter] I grew up in a household where the political was a key component of everyday life. My father was a newspaper reporter and my mother was a school teacher and also worked for a non-profit organization. They were both involved in anti-war movements in the late 1960s in Chicago. I grew up with that legacy. With that background, I had great difficulty navigating my way through the world without thinking about the ways in which the political affects everyday interactions. When I sit down to write a book, the political is always influencing my creative impulses. I think my books tend to be very broad and complicate realism, while still telling stories about the world we live in.

At times I Am No One uses long, elegant sentences with digressions, but they never lose the reader, and always return to where they began. Who are your literary influences?

There are a great many. [Laughter] For this book, I was thinking about a few writers in particular. I’ve been trying to read Proust in French, having read the first two volumes in English. His circumambulatory style influenced my prose. The Spanish writer Javier Marias is also an influence. And then there’s someone like Nabokov. I was reading Lolita before I began working on this book.

I also wanted prose that would speak to the style of the character, Jeremy.

Yes, professorial and intellectual.

Even a bit pedantic.

Yes, somewhat self-important but still quite likable in his own way. [Laughter] Which leads to the next question. At times, Jeremy O’Keefe seemed the proverbial unreliable narrator, but was he merely unwilling to look at himself more deeply?

I think that’s a really interesting way of thinking about him. He’s not trying to mislead the reader as often occurs with unreliable narrators. What makes him unreliable is his inability to see his own self in the world and his not being able to see the ways in which he’s failed, both professionally and personally. I agree with you: his unreliability derives from his failure at introspection.

That leads me to another question. The novel seems to be partly metafiction in the sense that Jeremy is very aware of writing a chronicle about his experience.

The books I most enjoy reading are those that are conscious of their status as books. That’s not to say I don’t enjoy reading books where metafiction isn’t in play. But I find the playful self-consciousness of a book very satisfying. So, I write the kind of books I would like to read. I’m interested in the way metafiction can take political energy and do something concrete with it.

You’ve studied both film and literature, and you’re a novelist. Talk about storytelling in film as compared to the novel.

The storytelling tools I learned at NYU’s film school were important in ways I could never have foreseen. Film chiefly taught me to build a kind of visual sensibility. Even when I’m thinking about the world within the confines of prose fiction, I’m always thinking about the visual setting.

I’m currently trying to write a screenplay. It’s a completely different kind of creative work. You have to resist those impulses to describe setting or describe a character’s interior thoughts and feelings. In film, you have to find ways to focus only on action and dialogue, yet convey the depth you can portray in a novel. It’s challenging.

Film forces the writer to conform to the proverbial axiom of ‘show, don’t tell,’ doesn’t it?

Absolutely. You have to show everything, right up front. It has to be done by showing action, setting and dialogue.

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned about writing?

First, the process of reading is never finished. You must read whatever is published in your genre and must read and re-read your own work in progress. I learned to appreciate how the process of reading and re-reading one’s own work helps clarify issues of both plot and style.

You’re hosting a dinner party and can invite any five guests, living or dead, real or fictional, from any walk of life. Who would they be?

[Laughter] I’d like to invite Stanley Kubrick. Then, I’d have Ruth Bader Ginsburg there. A fascinating guest would be William Faulkner. I’d also invite the late Bill Cunningham, along with Elena Ferrante because I really enjoy her work.

Congratulations on writing I Am No One, a superbly-written and elegant novel exploring multiple themes involving political surveillance, human nature, consciousness, relations between people, and the role of culture in forming a person’s identity.