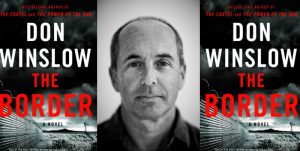

Don Winslow, the acclaimed author of The Winter of Frankie Machine, Sav ages, The Force and other literary crime novels has completed his internationally bestselling trilogy which includes The Power of the Dog, The Cartel, and his just published novel, The Border.

ages, The Force and other literary crime novels has completed his internationally bestselling trilogy which includes The Power of the Dog, The Cartel, and his just published novel, The Border.

For forty years, Winslow’s protagonist, Art Keller, has been on the front lines of America’s longest and most deadly conflict: The War on Drugs.

The heroin epidemic is still the scourge of America, and now, Keller is not only at war with the cartels, but with his own government. The story hurtles from Mexico to Wall Street, from the Guatemala slums to the corridors of Washington, D.C. and the highest levels of government. This final installment of the trilogy is brutal, humane, soul-searching, and resonates with the story of America today. This sprawling conclusion of the trilogy has been praised by Stephen King, Michael Connelly, Lee Child, Dennis Lehane and others.

Mark Rubinstein: “This trilogy is “the work of my life,” is the way you describe the twenty-year odyssey which concludes with the publication of The Border. How did this begin and how does it feel now that you’ve completed this journey?

Don Winslow: It began in 1997 when there was a massacre of nineteen men, women, and children in a little town in Mexico, not far from where we used to go on weekends. At that time, I knew nothing about drugs, and couldn’t understand how the drug trade had gotten to the point where someone was willing to murder nineteen innocent people. Mind you, by today’s standards, that’s a low body-count.

I never started out to write The Power of the Dog. I was reading philosophy books, trying to get an answer to this question about human brutality. I then began reading the history of Mexico and drug trafficking; and the more I read, the angrier I got. I eventually typed out Dog.

How do I feel now? It’s a very strange feeling not to be getting up and going to the drug news or news about Mexico. Some of my characters exist through all three books. I’ve been with them a long time. There are times when I read the news and ask myself, What would Keller think? [Laughter]. I have to remind myself he’s not real. It’s been a bittersweet thing to let go of that world.

Mark Rubinstein: To say The Border is a sprawling multi-faceted tale is an understatement. It involves crime, corruption, politics, greed, and human nature. Rolling Stone called your trilogy, “A Game of Thrones of the Mexican drug wars” Did you intend to write an epic series of novels?

Don Winslow: After The Power of the Dog, I swore it was over for me. It was a grueling topic to research. A few years later, I found myself writing The Cartel, which was far tougher to write because of the ever-increasing level of violence, sadism, and insanity of the drug world. It was a virtual reality tour of hell to write it each day. I thought—stupidly—there was no more story to tell. Unfortunately, there was a lot more story. But I never set out to write a multi-volume saga.

I now understand completely the nature of addiction. [Laughter]. It was a compulsion. I couldn’t step away from the topic.

Mark Rubinstein: At the outset of The Border, there’s talk of the heroin trifecta. Will you tell us about that?

Don Winslow: After spending time talking with addicts, I learned so much about the heroin epidemic. Of course, I’m aware that opiates are an answer to pain. In fact, the word ‘heroin’ derives from the German word for ‘hero’ because it was designed to treat wounded soldiers. It’s been around for a very long time. The Odyssey makes reference to it in the Land of the Lotus Eaters. It’s always been used in response to pain, often beginning with an attempt to treat physical pain. But, opiates are used more often for problems other than physical pain. Regardless of why they’re used, people develop a tolerance and dependence on them.

What kind of pain makes the U.S., with only 5 percent of the world’s population use, 80 percent of the world’s opioids? It’s partly physical, but it’s mainly psychological, and there’s a huge economic component to this. Poverty and drug-use go hand in hand. There’s an opiate scourge in the U.S. because so many people feel left behind. Opiates kill the psychic pain for a while, but of course, they create different and worse pains. So, the heroin trifecta is physical, emotional, and economic pain.

Mark Rubinstein: A character in The Border says, “The difference between a hedge fund manager and a cartel boss is the Wharton Business School.” Tell us more.

Don Winslow: [Laughter] That’s how it feels. Big Pharma originated the opioid epidemic largely out of greed. The same people who invented Bayer aspirin invented and sell opiates. When we compare the capitalists and the cartel leaders, the financial guys wear suits and are better educated, but they’re both in the drug business and the money business.

The drug money has to go somewhere. The cartels don’t file tax returns, but each year we send between 60 and 100 billion dollars to Mexico in exchange for illegal drugs. That money comes back to the U.S. as investments in legitimate businesses. If we think we’re so clean, that’s an illusion. That liquid money comes back into real estate and the banks.

Mark Rubinstein: The novel describes the harrowing descent into criminality of a Guatemalan boy, Nico. How did you learn so much about this phenomenon?

Don Winslow: By reading books, meeting journalists and talking with people. I wrote this book before the alleged crisis of migrant caravans at our southern border was an issue. I wanted to let the reader see these headlines on an individual level. It’s a realistic depiction. Nico grows up amid the horror of Guatemala and makes it to Queens, New York, where he finds the same gang he was running from in Guatemala rules the streets where he now lives.

Mark Rubinstein: The Border describes, among many other issues, the fact that a border wall won’t do a thing to stop drugs from coming into the U.S. This resonates profoundly with our political turmoil right now. Will you explain what you mean?

Don Winslow: Ninety-five percent of the illegal drugs coming across the Mexican border come through the legal points of entry. Mostly through three points: San Diego, El Paso, and Laredo. They come in tractor trailer trucks, and to a lesser extent, in automobiles. Roughly 4,500 trucks come through those points each day. In El Paso, one comes through about every fifteen seconds. There’s no way to search every tractor trailer truck for a kilo of heroin. These aren’t my numbers; these are the DEA’s statistics.

The traffickers themselves have just told us this in the Chapo Guzman trial. In the trial, major traffickers, one after another, testified to this point. A wall 100 feet tall, 100 feet wide, and 100 feet deep won’t make a difference because 95 percent of the drugs the drugs are coming through these legal points of entry. Why? Because these legal, guarded border crossings lead directly to the U.S. highway system.

If Donald Trump wants Mexicans to pay for the wall, he’s talking to the wrong Mexicans.

The cartels would happily give him the money—and believe me, they have it. If that wall is built, the little bit of drug trafficking done by minor players, who are unaffiliated with the cartels, might be interdicted. They’d be forced to bow down to the cartels and pay them to use the gates in those trucks.

The small players would have to go to the big players, who would make more money, and quickly make back the money they would have spent to build Trump’s wall.

It’s too bad The Border, the most timely novel I’ve ever read, isn’t in the hands of every member of Congress. The book is not only a powerhouse crime thriller, but is a primer on the realities of the drug trade, on corruption, immigration, our politics, big business and their intersection in our tumultuous times.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.