Known to millions of fans, Don Winslow is an author of crime and suspense novels, including a series of five novels featuring private investigator Neal Carey as the protagonist. His highly acclaimed standalone novels include Savages, The Winter of Frankie Machin e, The Death and Life of Bobby Z, The Power of the Dog, and The Cartel.

e, The Death and Life of Bobby Z, The Power of the Dog, and The Cartel.

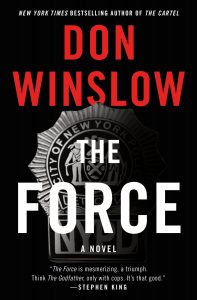

The Force, his latest novel, features Detective Denny Malone, a NYPD sergeant who’s head of Manhattan North’s task force for narcotics, dubbed “Da Force.” For 18 years, Malone has done whatever it takes to serve and protect a city of glitz, glamour, depravity and corruption; a city where no one is clean—including Denny Malone himself.

Very few people know that Denny Malone and his partners have stolen millions of dollars in drugs and cash in the wake of the biggest heroin bust in the city’s history. But now Malone is snared in a trap of competing forces, and must thread his way through conflicts that may involve betraying his brothers and partners, the Job, his family, and the woman he loves.

“The Force” is a mesmerizing novel: part police procedural, and crime novel; and part, epic tale. It’s a searing and soul-searching depiction of a tortured NYPD detective. You said, ‘This is the book I’ve wanted to write my whole life.’ Tell us about that.

I was born on Staten Island where Denny Malone lives. I was raised in Rhode Island but as a kid I was always running down to New York. I lived and worked there in the late seventies and early eighties. New York has always been a home to me.

York. I lived and worked there in the late seventies and early eighties. New York has always been a home to me.

But it’s more than that: the movie The French Connection is one of the reasons I’m a writer. I remember distinctly going into the theater on Broadway and seeing that film. I was just blown away by it, and by Serpico followed by Prince of the City. Those were important and evocative works for me, both the books and the films. Having lived and worked in New York and having been so influenced by those movies, I always had an ambition to try writing this book.

In “The Force,” Denny Malone is a conflicted man: he uses drugs, is separated from his wife, feels guilty about his kids, and lives on the edge. Many of your protagonists can be described as ‘messed up’: Frankie ‘Machine,’ Ben and Chon from “Savages,” and Tim Kearney aka Bobby Z. How do you manage to dig so deeply and depict such flawed and troubled people?

Those kinds of people are more interesting. The edge is always more interesting than the center. I recall Michael Connelly and I were at some conference and he was talking about writing. He took a cup and put it on the center of the table. ‘It’s not very interesting now,’ he said, and kept moving it toward the edge to the point where it was about to fall over and shatter. And then he said, ‘Well, now I have your attention. Now, it’s interesting.’

He was dead right about that. He was talking more about action than about character, but I’ve always taken that concept and applied it to character. I think one of the great advantages we have in our genre of crime fiction is we write about people in extremis. We write about people in extraordinary situations. And, we write about flawed people. Before this, I wrote more about criminals than cops, but it’s the same principle. The flaws in these people make them interesting and compelling. At the end of the day, the flaws make us love or hate them.

You and I have been married a long time. You know that you get into a relationship because of someone’s virtues, but after a while you begin to love their flaws. I often feel that way about my characters. I come to love them in spite of and because of their shortcomings. I often think our greatest strengths are also our greatest weaknesses.

That’s true of Denny Malone: the same things that drive him to do great things, also drive him to do bad things.

You have an extraordinary backstory. You’ve been a movie theater manager, a private investigator, led photographic safaris in Africa, hiking expeditions in China, and directed Shakespeare productions in Oxford, England. How have these experiences informed your writing?

I think—and you know this, too—everything we do informs our writing. That’s what makes us writers. Everyday observations and experiences become grist for the mill. More specifically, I grew up on Shakespeare. I was reading and memorizing Shakespeare when I was eight years old. Having the chance to work with great people in England, working with language every day as a director, I had to make the language understandable and physical. I had to bring out the muscularity of the language. It definitely helped inform my writing. My involvement with the theater company was mostly before my first novel was published. I was still struggling to make a living. From seven in the morning until ten at night, I was either rehearsing Shakespeare, teaching it, or talking with other directors. I was constantly immersed in language—with its rhythm, sound and with dialogue, all of which was a tremendous foundation for my writing.

The investigative work was not terribly different from what I do now, in the sense that I looked at lots of trial transcripts, read records, and interviewed people. I developed a capacity to search out certain details, looking for things that didn’t quite match-up. I looked for discrepancies between documents and testimony. That background informs my writing. For example, while writing The Cartel and Power of the Dog, I went through thousands of pages of records. Those were skills I learned as an investigator.

As a photographic safari guide in Kenya, my job was to notice details. For instance, when trying to find a leopard for people to photograph, I had to keep in mind there would be a certain kind of tree at one time of day, and another place at a different hour. In other words, I was always looking at details. I become a trained observer and would look at underlying reasons for things being the way they are.

In crime writing, there are the events, but then there are the underlying reasons for what has happened. Providing that richness is what I hope to give the reader.

As do “The Power of the Dog” and “The Cartel,” “The Force” explores, among other things, the drug trade, politics, police, and corruption. What has drawn you so intensely to these issues?

I never started out to write about the drug world and these issues.

I live near the Mexican border, and back in the late nineties, a massacre occurred just across the border. I wanted to understand why it had happened. I found myself sitting at the keyboard and writing about it.

Living on the Mexican border, I eat more tortillas than bread [Laughter] so it’s very real for me. In the course of researching and writing about it, I’ve met people who keep it vivid for me. It’s one thing to talk about the heroin epidemic, it’s another to go to the funerals.

As a writer, you want to write about the most interesting and important things happening today. I want to write about race relations, about police shootings, corruption and drugs. In life, you can’t separate things from each other; they’re all interconnected parts of a larger piece.

Did growing up in Rhode Island also influence you?

Rhode Island had a large Mafia presence, more so when I was growing up than it does now. It was always around, and I saw it. It was always written about in the Providence Journal, and Jimmy Breslin was a big influence on me. I recall being in high school and reading Breslin’s columns and thinking that’s what I want to do. In college, I was a journalism major. I wrote columns basically imitating Breslin’s style [Laughter].

Is there anything about your writing process that might surprise our readers?

I don’t know if it’s a surprise, but I treat writing like a job. I don’t really believe in inspiration. Inspiration is for amateurs.

You know the old saying, don’t you? ‘If you wait for inspiration, you’re a waiter, not a writer. [Laugher]. You can wait on tables at Le Cirque or at a diner, but you’re still a waiter.’ [More laughter]

Let me tell you a cute story about Le Cirque.

Years ago, while working as an investigator, I stayed at the hotel where Le Cirque was located. But I wasn’t going to eat at that restaurant, not at those prices. So, I ordered in some Chinese food. When I got my hotel bill, there was a forty-seven-dollar surcharge for them having let the delivery guy come up to my room with the food. So, the next time I stayed there, I ordered the food and asked the delivery guy to meet me in the hotel lobby. I ate the take-out in the lobby, right outside the entrance leading to Le Cirque. I stood there with a brown paper bag and ate the Chinese food. They told me it looked seedy and asked me not to do it. So, I negotiated with them and they dropped the surcharge.

But getting back to the writing: to me, it’s a deliberate process. It’s not based on inspiration. The other thing that might surprise our readers is I don’t start writing a book until I know the main characters well. I’ll think about them—sometimes, for years, like in the case of Denny Malone.

How did writing “Savages,” the novel, differ from teaming up with Shane Salerno and writing the screenplay for the movie?

They’re two different breeds of cats. One is static, the other is kinetic. One has plenty of time for the story to unfold, the other is on a clock. In a movie, you have to make a scene do five or six things simultaneously. That can be difficult for a novelist.

I understand that “The Force” has been sold to Fox with James Mangold directing, and Ridley Scott is directing “The Cartel,” which is going to be a film. How have these events impacted your career?

For me, it’s been huge. To have directors of that stature is fantastic, and that sunlight reflects on me. The major effect is I now have the economic freedom to write all the time. That’s been true since The Death and Life of Bobby Z was made into a film. I was six published books into my career before I could quit my day job. I always made a living. I wasn’t going to penalize my family for my ambition, but as for how I approach my day? It’s always been the same: Get up and show up.

“The Force” reminds me of “Savages,” which I still view as one of the most audacious pieces of contemporary fiction I’ve read. Both books are written in an edgy, lyrical, cinematic, even radical style. Will you talk about your writing style?

As in architecture, form follows function. I think story dictates style. I try to write from inside the character’s head. It’s kind of sneaky: it’s third person but it has a first-person point of view. Does that make any sense?

Yes, it does. And it’s written in the present tense, which gives everything a sense of immediacy.

Yes, when I began writing in the present tense, the story suddenly had a sense of immediacy it never before had. It was not like I was looking down at a table and describing what was there. So, I’ve stayed with writing my novels in the present tense. That way of writing lets me inhabit a character. It dictates the style, the rhythm and the choice of words. This may sound pretentious, but I try to pay attention to the musicality of the writing.

It doesn’t sound pretentious at all. There is a music to the words.

Yes, there is. I go back to Shakespeare with that concept. You have to stage it, you have to put it on, you have to hear it. Sometimes when I was writing some of the chapters in The Force, I would listen to the hip-hop music referred to in the chapter, and pump it up to the point where it was painful. I’d write while the energy and edge and anger of the music was pounding in my head. In other scenes, I’d listen to the jazz referred to in that chapter I was writing.

I think readers love being there in the midst of the action. That’s particularly true in the crime genre. There’s a powerful link between film and novels, especially in noir fiction.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers today?

I’d simply say: Write. Like most things in life, it’s a verb before it’s a noun.

The second thing I’d urge is: Don’t write anything unless you have to. I would say you shouldn’t write unless you feel an inner compulsion to do so. And then, don’t listen to most people.

The third bit of advice is simple: just read. Read good books. I just finished War and Peace for the fifth time in my life. I wanted to see how a great writer handles a multi-generational story. So, one has to read good things.

Another pointer: Don’t pay attention to so-called peer-reviews. It’s too easy to get nibbled to death by ducks. [Laughter].

I’d say one other thing: there’s a difference between a writer and an author. An author is published. I would say to any writer, if you sit down and write something and finish it and wrestle with it, you’re a writer. And don’t let anybody ever tell you you’re not a writer. And you’ll have my respect as a writer. Welcome to the brotherhood and sisterhood.

Other than writing about crime, what do writers like Michael Connelly, Lee Child, John Sandford, David Morrell, Laura Lippman, Reed Farrel Coleman, Patricia Cornwell, and so many others have in common?

I think these writers and so many others like them share something important: a great sense of humanity. I think they know people and love to explore what humanity really means in terms of language, story, and in terms of place.

Will you compete this sentence: “Writing novels has taught me___________?”

Tenacity. It’s taught me tenacity [More laughter]. It’s a marathon. It’s like I’m at mile twenty-two and think, I’ll never make it. And you feel the same way the next time, but now you have the experience and can tell yourself you got through it last time and you’ll get through it again. And it will come out pretty well.

What’s coming next from Don Winslow?

I’ll probably write another book. [Laughter].

Congratulations on writing “The Force,” a brilliant novel, rich in language, conflict, setting, and character. It resonates deeply with realism, honesty, and sheer magnetism. Fans of “The Godfather,” “Mystic River,” “The Wire,” and “The Departed” will absolutely love this book.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.