Nathan Hill’s stories have appeared in various literary journals and he has won or been nominated for many prestigious prizes. He is an Associate Professor of English at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he has taught creative writing and liter ature courses He has worked as a newspaper and magazine journalist, and holds a BA in English and Journalism from the University of Iowa and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

ature courses He has worked as a newspaper and magazine journalist, and holds a BA in English and Journalism from the University of Iowa and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

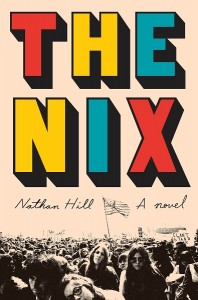

The Nix, his sprawling, multi-tiered debut novel, is ostensibly about a young English professor and failed writer, Samuel Anderson, who undertakes reconstructing the life of his mother who abandoned him when he was 11 years old.

But from the realm of disturbed family dynamics, to youthful friendship and romantic obsession; to the radical Sixties, to Norwegian ghosts, politics, video gaming, academia; to the Vietnam and Iraq wars; to secrets and lies, and to many other things, the novel is about much, much more. It examines the idea “the things you love the most will one day hurt you the worst.”

I understand between research and writing The Nix, it was ten years in the making. Tell us how it came to be what it is now.

I was doing some very poor work during the first couple of years writing it. I started the novel in 2004 as a young man straight out of an MFA program. I wanted to write something that would give me the kind of career I’d imagined for myself. I was writing crap. When you write to impress agents and editors, you’ll write bad prose. My writing didn’t have any personal human truths. I was rejected everywhere, as I should have been.

I floundered for a couple of years. I was doing research but was also trying to figure out what kind of book I wanted to write. I moved from New York and took a teaching job in Florida, having dropped out of the whole publishing query letter-writing scene. I was teaching and playing a lot of video games, and was sort of mentally marinating for a long time.

I then thought I’d missed my chance at being published, so I decided to take that anxiety about ‘blowing it’ and put it into the book. I included some experiences I was having teaching as well as with video games. When I decided to tell a true human story, the writing took off. I had to tear down my preconceived notions about what a successful writer should be and simply became the writer I needed to be.

It’s difficult to pick out my favorite sections of the novel, there were so many, but I absolutely loved the interplay between Samuel and his student, Laura Pottsdam. I know you spent years in academia, so tell us what Laura epitomizes.

When I was teaching, there were a lot of Laura Pottsdams in my classes. She’s an amalgam of some students I dealt with. While most college students are hard-working and want to learn, there’s a number of students who will plagiarize, cheat and not feel badly about it. They won’t do the reading, and have trouble paying attention to anything besides their phone, and will ask about the utility of what they’re learning. ‘Why do I need to know Hamlet in real life?’… questions like that.

Frequently, that attitude, combined with a sense of entitlement since they’re paying tuition and feel they deserve to get a great job, is reinforced by parents who will provide a last measure of self-defense when the students get into trouble. Just Google the term plagiarism epidemic and you’ll know exactly what I’m describing.

As often happens, when I write and spend enough time with a character, I began to ask myself questions about Laura, which in turn made me realize something was going on with my students that made them fundamentally different from the way I was in college. I realize the world has changed—drastically. My students grew up during the Great Recession. Teachers and parents tell them it’s a competitive marketplace, not only here, but worldwide. Corporations won’t look out for them. Students now are enormously anxious about getting a job and moving out of their parents’ homes. The assumptions I could make sixteen years ago—about finding a job and living independently—no longer hold.

Today’s students feel they need to excel in everything, so some of them cheat. Once I understood that, Laura Pottsdam became a more sympathetic character for me.

The Nix has a kaleidoscopically sweeping quality, zooming from 1968 to 2011, then back to 1944, and is told from multiple points of view. How did you manage to organize this wonderful sprawl?

My first draft was one-thousand and two pages long. [Laughter] I chipped away about four-hundred pages. It was so long because I gave myself permission to go down whatever rabbit hole or cul-de sac I imagined. I figured I might as well entertain myself in the writing of this book.

If I don’t ask you about one chapter, I’d be remiss. The Nix has a ten-page chapter that’s one-sentence long. Tell us about that.

I started writing that chapter as depicting the day Pwnage—the video game guru—would stop playing video games. Then, I started listing all the reasons he couldn’t stop playing. I read the rough draft to my wife who asked ‘Is this all one sentence?” It struck me that maybe it should be one sentence. I wanted to capture how time could slip away when you’re so engaged in something. Pwnage was feeling claustrophobic and anxious. At that point, the video game was the only thing giving his life meaning and substance. I wanted to textually replicate his anxiety in the reader.

Critics have likened The Nix to works by John Irving, Jonathan Franzen, Michael Chabon, Donna Tartt, Thomas Pynchon, among others. How does that make you feel?

[Laughter] Obviously, it makes me feel wonderful. How could I not feel great about it?

Does it make you feel burdened by expectations about whatever comes next?

I’m looking forward to getting back to the material for my second book. After all the attention this book is getting, I still have to go back and face a blank page. That blank page doesn’t give a damn what the New York Times said about me.

Yes, it’s gratifying people are saying such nice things about the book, but when I go back and start working again, I have to forget about the praise.

The Nix contains reflections on the misguided literary ambitions of a young man who wants to write for the prestige and social recognition it will get him. Will you talk about that?

Samuel wants to write because he thinks it’s going to make people like him. In college, I tried using my writing to impress women, and it’s shocking how poorly that worked. [Laughter] I tell my creative writing students to write because you need to. There should be something about the activity itself that’s valuable. Writing for recognition, ego, or praise guarantees you’ll write poor stuff.

In some ways, I think writing a novel should be like planting and tending a garden. People don’t keep a garden to get famous. A garden isn’t a failure if thousands of people don’t look at it. A gardener loves gardening because it brings a measure of joy. The writing of this book brought me a great deal of joy. If there’s humor in the book it’s because I think a pre-requisite for setting a scene is it must delight me in some way. I feel it’s a healthier way of writing than the way I approached it as a young man. Being published, I think, should be viewed as a side-effect of the writing.

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned about writing?

I once handed in a story in a creative writing class. The teacher looked at it and said, ‘You can do this, but you’re going to die soon, so you might as well write something that really matters.’ That was good advice. I think of that incident when I’m writing.

You’re hosting a dinner party and can invite any five people, real or fictional, living or dead. Who would they be?

That’s a cool question. I’d stick with writers and set up a literary salon. I’d invite Virginia Woolf, Donald Barthelme, David Foster Wallace, James Baldwin, and Gertrude Stein. I would just cook and listen. Now that would be a fun party!

What’s coming next from Nathan Hill?

I’m working on a new novel. I have a premise and characters. I don’t as yet have a plot, but that will come. I’ll be writing about the things that interest me. Right now that happens to be marriage, authenticity, gentrification, and the nineties. We’ll see what that turns into. [Laughter]

Congratulations on penning The Nix, a soulful, hilarious, profoundly penetrating novel so brilliantly written, it took me on a head-spinning ride across a fantastic literary landscape.

Mark Rubinstein’s latest book is Bedlam’s Door: True Tales of Madness and Hope, a medical/psychiatric memoir.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.