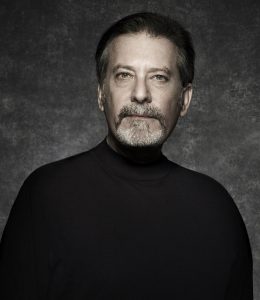

Jonathan Kellerman, the bestselling author of forty-one crime novels, is known to mystery-lovers everywhere. With a doctorate in psychology, Jonathan has applied his knowledge not only to his novels, but to those he has co-written with his wife Faye, and son, Jesse. All three of them are bestselling authors. Additionally, he has written two children’s books and many nonfiction works, including Savage Spawn: Reflections on Violent Children, and With Strings Attached: The Art and Beauty of Vintage Guitars. He’s won the Goldwyn, Edgar, and Anthony Awards, and has been nominated for a Shamus Award.

son, Jesse. All three of them are bestselling authors. Additionally, he has written two children’s books and many nonfiction works, including Savage Spawn: Reflections on Violent Children, and With Strings Attached: The Art and Beauty of Vintage Guitars. He’s won the Goldwyn, Edgar, and Anthony Awards, and has been nominated for a Shamus Award.

Heartbreak Hotel, is the latest novel in Jonathan’s acclaimed Alex Delaware series. Along with Sue Grafton’s “Alphabet series” The Alex Delaware series is one of the longest running on the literary landscape.

Heartbreak Hotel begins with nearly one-hundred-year-old Thalia Mars asking Alex to come to her suite at the Aventura, a luxury hotel with a checkered history. Thalia asks him questions about guilt, criminal behavior and victim selection. When Alex inquires about her fascination with these issues, Thalia promises to reveal more in their next meeting. But when Alex shows up the next morning, Thalia is dead in her suite.

Alex and homicide detective Milo Sturgis find themselves peeling back many layers of Thalia’s long life, and nearly a century of secrets slowly emerge—secrets that unleash an explosion of violence.

Alex Delaware has evolved over the years. Tell us a bit about that evolution.

It’s funny because it wasn’t a conscious decision to have Alex evolve over time. People reading the earlier books are in a better position than I am to see the changes in him. I rarely read my earlier books unless I’m doing research for accuracy. My son, Jesse, said the earlier books are a bit more literary, there’s more verbiage and description in them than in the later novels.

While I don’t age Alex in real time, he’s mellowed out over the years. Maybe you’re the better judge than I am. Maybe he’s mellowing as I’ve mellowed over time. [Laughter]. I must say, I don’t want him to lose his edge. I still want him to be compulsively driven because that’s what drives a crime novel forward. I don’t think there’s anything more boring that a crime novel in which the protagonist is really laid back.

The dialogue in Heartbreak Hotel is edgy and realistic. Talk to us about the importance of dialogue in your novels.

Dialogue is interesting. When I first started writing novels, I felt creating dialogue was a weakness of mine. I thought my strengths were playing with language and description. I’m a visual person. I’ve been a serious artist for most of my life. I was able to paint and draw like an adult when I was ten. I tend to perceive the world in a visual manner.

My wife Faye is an auditory writer. She has an amazing ear and can imitate people after hearing them speak once. I learned to write dialogue from Faye, and from reading Elmore Leonard. I realized when you write dialogue, it must sound like people talking. But of course, it’s not like people talking because when they talk, the conversation is replete with ‘ums’ and ‘ahs’ and pauses. Dialogue in a novel is an artifice in which you construct a false reality. I learned to keep it snappy and to open my ears to what people say and how they say it. The rhythm of dialogue came easily to me because I’m a musician and understand cadence and timing. Over the years, I’ve tried to make the dialogue better, because I don’t want it to seem stale. I think I’ve improved writing dialogue by listening to people talk and by keeping the dialogue brief, avoiding too much running on and on.

In Heartbreak Hotel, Alex’s internal thoughts and descriptions often reflect on issues larger than the novel itself. An example: “Some cops toss a room with the abandon of deranged adolescents. My friend’s grooming may come across as hastily assembled but he puts things back exactly where he found them.” Your novels not only tell a story, but serve as a vehicle for commentary about life. Tell us about that.

I think that’s just naturally the way I see the world. You as a psychiatrist and I as a psychologist must acknowledge we got into this field because we see things in multiple dimensions.

I never set out to write a ‘message book,’ but things concern me, and by dealing with larger issues, I hope to elevate the story beyond it being just a good crime novel. And, I call what I write a ‘crime novel’ rather than a mystery, because the story is always propelled by the crime.

Of course, my experience as a psychologist informs my writing. For example, as someone who worked with children in oncology, an event like a terrible cancer diagnosis can become a catalyst for unlocking all kinds of other issues. That awareness colors my writing in the sense that a specific crime can open up a Pandora’s box of reactions. Every crime impacts people, and trauma can bring out the best or worst in them, whether in a novel or in real life.

Alex Delaware had a difficult childhood. As psychologists, both he and you know the indelible effects of the past on current functioning. How does Alex’s past affect his present life?

I developed and evolved Alex’s past as I got to know him better by writing books about him. When I wrote the first one, When the Bough Breaks, which was published in 1985, I had a certain notion back then about Alex. I never thought I’d get published or that it would become a successful series. I learned about Alex along with my readers, and things began falling into place. I parcel his childhood and all of Alex’s personal history into the books very judiciously. In some novels, he’s a protagonist; in others he’s a consulting psychologist. Of course, his past has impacted his interest in psychology and in wanting to set certain things right.

You once said, “Psychology and fiction are actually quite synchronous.” Tell us more about that.

I think both involve attempts to better understand people.

As a psychologist, I love my work because I learn about people and what drives them.

As a writer, I get to play God by creating characters, and then get to see how they react to difficult situations.

What unifies psychology and fiction is they are both avenues to explore more about the human condition.

If you could read any one novel again as though reading it for the first time, which one would it be?

“I’ve never been asked that question. [Laughter] That’s a tough one. The Count of Monte Cristo was the seminal novel in my life. I read it as a youngster. It struck me as an amazing book. There was so much going on: adventure, comradery, relationships and revenge.

What’s coming next from Jonathan Kellerman?

I’m working on the next Delaware novel. Jesse and I have a book coming out called Crime Scene. It’s the beginning of a new series. I always wanted to write a novel about a crime scene investigator, which is what this novel concerns. Jesse and I wrote it together and we’re now outlining the second one.

Congratulations on penning Heartbreak Hotel, another Alex Delaware mystery that goes far beyond its genre. It’s a compelling psychological crime novel with deeply imagined characters told in a literary style that kept me turning pages to the very end.

Mark Rubinstein’s latest book is Bedlam’s Door: True Tales of Madness and Hope, a medical/psychiatric memoir.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.