Reed Farrel Coleman, a bestselling author of many novels, has penned the popular Moe Prager series, the Gus Murphy novels, and other well-received books. He’s a three-time winner of the Shamus Award, and has won the Macavity and Barry Awards, among others.

Robert Parker, considered by many to have been the dean of American crime fiction, was the author of seventy books, including the series featuring Chief Jesse Stone.

After Parker’s death in 2010, Reed Farrel Coleman was chosen by the Parker estate to keep this immensely popular series alive.

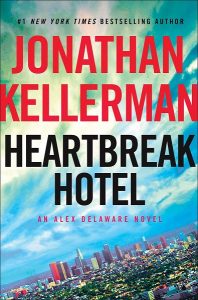

In The Hangman’s Sonnet, Jesse Stone, Paradise’s police chief, is still reeling from the murder of his fiancée by the crazed assassin Dr. Peepers. Jesse learns a gala 75th birthday party will be held in Paradise for folk singer Terry Jester, who has spent the last forty years in seclusion after the mysterious disappearance of a recording of the ballad, The Hangman’s Sonnet.

Suddenly, an elderly Paradise woman dies while her house is being ransacked. What were the thieves looking for? And what, if any, is the connection to Terry Jester and the missing recording? The bodies begin piling up and the town’s mayor fears a PR nightmare. Jesse must connect the cases before more deaths occur, and the town of Paradise becomes a killing ground.

In “The Hangman’s Sonnet” Jesse is mourning the death of his fiancée, which connects thematically to Gus Murphy’s plight in that series. You write about bereavement quite vividly. Will you talk about that?

Putting myself in other people’s shoes and imagining situations different from those in my life are exercises I enjoy.

I’m quite sanguine and philosophical about life and death, although I’m sure I’d be devastated if a child of mine died. Intense grief leaves a person at their most vulnerable point, and renders them off-balance and without emotional reserve.

This heightened state is what good thriller writing is all about, and I try to capture the intensity of emotions my characters feel when they’re distraught.

“The Hangman’s Sonnet” has Jesse going to Boston to meet with a PI named Spenser, the protagonist of a Robert B. Parker series being continued by Ace Atkins. Did you confer with Ace about that portion of the book?

Yes, I did. Ace and I write about Robert B. Parker characters who are in overlapping universes. Also, Mike Lupica, the sportswriter, has been signed to write Sunny Randall novels. That means three of us who’re writing Bob Parker characters, have protagonists who exist in roughly the same universe. We must talk to each other because anything I do in a Jesse Stone novel might affect Ace’s writing of a Spenser novel. And I’ll be talking with Mike if our characters overlap.

Jesse attracts many different women. What about him is so alluring to them?

First of all, he looks like a young Tom Selleck. [Laughter]. Secondly, he’s the classic self-contained man who is very much to himself. And, he’s wounded. There’s a long tradition in literature of women trying to heal the wounded man. There’s a real pain in his soul and that’s very appealing to women.

There are elements of dark humor in your renderings of Jesse Stone. Will you talk about the role of humor in suspense/thriller fiction?

I have a somewhat cynical take on the world and that attitude is just part of hardboiled fiction. For me, when there’s no humor in a mystery or thriller, the book becomes turgid. It’s important to have humor in a story, even if it’s dark or cynical. There was always some humor in Bob Parker’s books—especially in the banter between Jesse and Molly. I’ve expanded it a bit because I’m not Bob Parker.

Jesse was a minor league baseball player until a shoulder injury cut short his career. Your descriptions of baseball are spot on. Is there a connection to your own athletic background?

There’s a connection to my own athletic dreams. [Laughter]. I was a jock; I played high school football and played a lot of organized sports. To this day, I play basketball five days a week. I feel that connection and understand how a guy like Jesse would judge himself by his athletic prowess. Many of the guys I grew up with judged themselves that way. I’m still an avid sports fan.

It was easy for me to imagine what it would be like for Jesse Stone to have been a great athlete and have an athletic future projected for you—to be one phone call away from becoming a Dodger—and then, suddenly, within a second, it’s all gone due to an injury.

The dialogue in “The Hangman’s Sonnet” is very realistic. Talk to us about dialogue in your novels.

Dialogue in novels is a kind of para-reality. No one really speaks like they do in books. People talk over each other; they go off on different tangents, and they repeat themselves all the time. I try to create dialogue as close to reality as possible, which is really a pseudo-reality. When you boil it down, no one would want to read an actual conversation between people.

My idea of dialogue is a kind of short-hand reality. You must move the plot along. No one wants to read a real, unedited conversation [Laughter].

What’s coming next from Reed Farrel Coleman?

I’ve already written the 2018 Jesse Stone novel. It’s called Robert B. Parker’s Colorblind. I wrote it before the last election, but it addresses a situation just like the one that happened in Charlottesville.

The next big project is this: I was hired by the film director, Michael Mann, to write a prequel novel to his magnum opus film, Heat. We hope it will generate a screenplay and a film.

Congratulations on writing “The Hangman’s Sonnet,” another high-octane and suspenseful Jesse Stone novel that keeps this engaging character alive for the enjoyment of millions of readers.