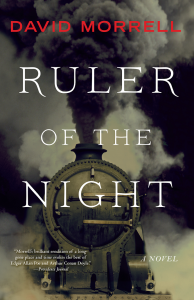

David Morrell is known to millions of readers worldwide as the “Father of Rambo,” the protagonist in his debut novel, First Blood. The recipient of many awards, David has authored 29 works of fiction that have been translated into 30 languages. A former literature  professor at the University of Iowa, he now presents us with the last in his Victorian trilogy, Ruler of the Night.

professor at the University of Iowa, he now presents us with the last in his Victorian trilogy, Ruler of the Night.

Set in 1855 London, Ruler of the Night once again features the brilliant Thomas De Quincey and his daughter Emily who this time must solve a murder which occurred aboard an English train. Set against the background of the Crimean War, the story details the tormented De Quincey’s confrontation with his most ruthless adversary.

Central to the novel is the building of the British railway system. How did this impact England?

The impact occurred over a brief interval of time. In 1830, the first railroad in England ran from Liverpool to Manchester and was only thirty-five miles long. By 1855, the railroad tracks covered six-thousand miles. It sped-up Victorian life from moving at ten miles an hour during the mail-coach era to fifty and sixty miles an hour. A newspaper at the time predicted the railway would “annihilate time and space.”

Before the railway existed, individual villages had their own times, based on sundials. The trains needed a uniformly reliable way to keep the schedules accurate, so each morning, the time (which was measured by the Greenwich Royal Observatory) was telegraphed to each train station. Thus, Britain had unified time. This was pivotally important in organizing and promulgating the Industrial Revolution.

The real-life Thomas De Quincey said “there was no such thing as forgetting, that the mind was like a page upon  which words were constantly inscribed and then erased and then inscribed again.” Tell us about that.

which words were constantly inscribed and then erased and then inscribed again.” Tell us about that.

De Quincey invented the term “subconscious.” As an opium addict, he suffered intense nightmares. Awakening from them, he would try reasoning where they came from in a way comparable to what Freud would do years later. De Quincey felt the human mind was filled with ‘chasms and sunless abysses and layer upon layer in which there were secret chambers where alien natures could hide undetected.’ His idea was that once an emotion or thought had been registered in the mind, it drifted downward into the subconscious where it remained, and we cannot forget anything. Another quote of his was ‘Memories are like the stars. They disappear during the day, but come out at night.’

Thomas De Quincey’s drug use parallels Sherlock Holmes. Drugs seem to be a classic element in mysteries of the era. Will you tell us about that?

There’s a direct link from De Quincey through Edgar Allan Poe to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Poe admired De Quincey’s work. In short stories like “The Fall of the House of Usher” you see that drug-like impression, where Poe imitates that aspect of De Quincey’s work. Of course, Poe invented the detective story in “The Murders of the Rue Morgue” where we have an eccentric private detective who has a sidekick recording his adventures. Conan Doyle acknowledged having taken that format from Poe and used it in the Sherlock Holmes stories. So, we can trace back Sherlock Holmes’ drug use through Poe and back to De Quincey.

Throughout the trilogy, and more so in Ruler of the Night, De Quincey is haunted by his past. How inescapable is our past?

De Quincey’s past is constantly bubbling up, and in a sense, controlling him. De Quincey sort of invented our notion of the autobiography. His best work is his writing about his own life and his attempts to understand himself, especially in Confessions of an English Opium Eater. In a sense, he was performing psychoanalysis on himself, and his thoughts about memories and one’s past are one of his major contributions to literature.

You’ve described the Victorian De Quincey trilogy as your “version of a nineteenth-century novel.” How did this differ from your other novels?

I was trained to think of a novel as consisting of form matching content. If you’re writing about something, you need to find a way for the form and content to match each other. With this trilogy, I did intense research about London in the 1850s. I wanted to convince readers they were truly on those fog-bound streets. I felt it would add to the atmosphere if I wrote the books as if they were Victorian novels. For years, I read extensively about 1850s London, and nearly hypnotized myself into that period.

I wrote the three books using techniques associated with the Victorian era—such as using the omniscient narrator and mixing the various viewpoints—I felt it would add authenticity to the way I was presenting the Victorian world. It would thrust the reader into the milieu I was creating on the page.

The De Quincey trilogy was a departure for you. What was your goal in writing these novels?

I wanted to escape the modern world. I started the research on Murder as a Fine Art in 2009, shortly after my granddaughter Natalie died at the age of fourteen from a rare bone cancer, Ewing’s sarcoma. Many years earlier, that same disease had killed my son at age fifteen. Unstrung by this double grief, I was seized by the notion to escape into 1850s London and try to hypnotize and protect myself from the reality of what had occurred. It was my attempt to escape from grief by disappearing into that world. A friend of mine said to me, “It struck me that Emily, De Quincey’s daughter is a version of Natalie. Whether you knew it or not, you were reincarnating your granddaughter in these novels.”

After having immersed yourself in Victorian England and the De Quincey saga, what feelings do you have about moving on to something else?

It’s been difficult. For years, I’ve been immersed in Victorian London. I feel as though I’ve come out of the depths of the ocean back into the modern world. Looking around at the vitriol of our current election cycle, it reinforced for me how much more pleasant it was to be in 1850s London. I must admit, I feel somewhat adrift right now.

What’s coming next from David Morrell?

I don’t know. I’m suffering from Victorian withdrawal. I’m catching up on my contemporary reading, and we’ll see where that leads me.

Congratulations on having written Ruler of the Night, the last of an exquisitely rendered and atmospheric trilogy reminiscent of Poe, which the Associated Press called “A literary thriller that pushes the envelope of fear…”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.