Meg Gardiner is the author of 12 critically acclaimed crime novels, including China Lake, which won the Edgar Award. Her best-known books are the Evan Delaney novels. Her latest novel is a taut and terrifying thriller, UNSUB.

UNSUB features Caitlin Hendrix, a detective, whose childhood nightmare reemerges: a serial killer known as the Prophet. He’s an UNSUB—an unknown subject—who again begins terrorizing the Bay Area after a hiatus of 20 years. This series of ritualized murders virtually destroyed her father who had been the lead investigator on the case back then. Caitlin is assigned to the case and must avoid making her father’s mistakes, or worse.

I understand you had some terrifying experiences that led to your fascination with unsolved serial murders such as those appearing in “UNSUB.” Will you share those experiences with us?

The first experience I had was as a child when I saw a police drawing of the Zodiac killer in my local newspaper. It was a picture of a gunman wearing a black executioner’s hood with the Zodiac symbol on its front. Seeing that drawing, I asked my parents what it was, and my father told me it was a picture of the infamous Zodiac killer who murdered people for the hell of it. As a little kid, it shocked and rocked me to think someone could do something like that. It kept me awake at night.

Only a few years ago, I found out there had been two double murders in the neighborhood where I grew up—a safe, easygoing suburban area in Santa Barbara, California. At the time, the murders hadn’t been linked, and it’s only been since the advances in forensic science that investigators determined these murders were committed by that same person: the infamous and still uncaptured serial killer who roamed California. He was first called the Night Stalker and is now called the Golden State Killer.

Learning there was a walking path between where these murders happened and where my brother’s family lived—two-hundred yards away—freaked me out. The crime scenes were directly across the street from his house.

Simply realizing how close these things can come to you, even when your world seems completely normal and safe—knowing someone is out there masquerading as a normal person who has a job, goes to your local supermarket, and has a nighttime hobby of rape and murder—is very unsettling.

Do you think that early, fearful experience of the Zodiac has expressed itself in your writing?

I think the idea that someone is out there when we would all like our worlds to be orderly and predictable left its mark on me.

“UNSUB” features a troubled and conflicted detective, Caitlin Hendrix. Tell us a bit about her.

Caitlin is young, ambitious, green, and haunted by the fact that her father, a homicide detective, had been dealing with this serial killer who destroyed him emotionally and tore his family apart. One of the reasons she’s become a cop and a detective was to be involved with this case, not only to bring the killer to justice, but also to redeem the family name.

Caitlin is a fascinating character. What characteristics make for a good protagonist?

A protagonist must have some burning desire—maybe for justice, survival, love, or passion. I want to explore what my main character both wants and fears more than anything else because that will affect everything she does. What is the protagonist afraid of losing beyond all else?

The serial killer in “UNSUB” is terrifying. What makes serial killers such fascinating subjects for crime fiction?

I think the public has a sense that serial killers are clever; their motives are mysterious; they don’t kill for money or revenge; they’re sneaky and crawl through the cracks while hiding from society. We all want to have a glimpse into the dark side of human nature. We want to try understanding why someone would engage in these kinds of killings.

You became a commercial litigation attorney and worked in that field before becoming a novelist. Tell us about your journey to becoming an author.

I wanted to write from the time I was a child. I grew up in a family of attorneys with fulfilling careers and love of the law. When I finished college, my father suggested that if I wanted to be a writer, I could write while I was half-starving, or I could write when I took a break from my litigation practice.

So, I went to law school. It was a fascinating, challenging and rewarding career. I had three small children and knew I needed a break from going to court, so I took a job teaching legal writing at the University of California. Ultimately, that was my gateway to writing fiction. I eventually escaped from law [Laughter]. I wrote short stories and magazine pieces while I was teaching, and attempted to write a novel, but had no idea how to do it.

Then, my husband was offered a job in London. We moved from Southern California to the UK. I had no job waiting for me and I was the trailing spouse [More laughter] as they called it in the expat community. The kids were out of diapers. I’d told myself I was going to write a novel and I decided it was time to put up or shut up. I wrote a terrible novel which I put away. Then I wrote another which was published in the UK. Then a few more were published there.

So, your novels were published in the UK. How did you become published and well-known in the U.S.?

I had a British literary agent who was shocked that I was published in the UK and almost everywhere else in the world, but not in the U.S. I’d written five books in the Evan Delaney series, but American publishers were uninterested in my fiction.

Then, an American author looked through his closet looking for a book to read on a flight to England. He found my book China Lake, which the publisher had sent him. He probably decided the print was large and easy on the eyes and he stuck it in his carry-on. He read it, and when Stephen King got off the plane, he decided he liked my novel. He read the rest of my books and didn’t understand why I had no American publisher. He kindly mentioned me on his website, urging people to look for my books. He then wrote a column for Entertainment Weekly, again mentioning my books. Strangely, within forty-eight hours of that column being published, fourteen American publishers were interested.

It was all due to the fact that Stephen King is an incredibly gracious and generous person. He supports other writers, artists and musicians and he uses his voice to bring attention to other artists. I’m eternally grateful to him.

You once said, ‘I put my demons on the page.’ What did you mean?

If something scares me, upsets or worries me, if it troubles my sleep, it’s likely to do the same thing to readers, and I can turn that into compelling fiction. I was once on a conference panel and another author said she writes to exorcise her demons. She felt it was cathartic. She asked me if I felt that way and I said, ‘I inflict my demons on my readers.’ [Laughter]. But I try to do it in an entertaining way.

You said you write crime fiction ‘because it gets to the heart of the human condition.’ Tell us more.

Crime novels—whether they’re thrillers, suspense books, or mysteries—always feature people facing the greatest challenges of their lives. Some evil has invaded their world, and chaos undermines everything they’ve known and they must rise to the challenge and put things right. The human condition, as I see it, isn’t about the English professor trying to suppress his crush on the sophomore coed.

A well-known critic once said crime writers lack real talent. You had an interesting response to that statement. What was it?

I thought the entire notion of talent was silly. The idea of talent being everything is really pernicious. The idea that if you don’t have sufficient talent you might as well just give up. As a writer and a parent, I think that can be undermining. Yes, talent is important, but on its own, it’s not enough. Hard work, training, dedication, observing the world, and putting in the work—sometimes joyfully, sometimes as a struggle—that’s how you get to be good at writing or any other endeavor. I said to the critic, ‘I once had talent, but I sold it so I could write a crime novel.’

Your blog is titled “Lying for a Living.” How come?

It’s labelled that because I get to make things up. Things come out of my imagination. It’s a little bit flip. Actually, I think fiction is the lie that tells the truth. The only lies on paper are non-fiction memoirs. [Lots of laughter]. Fiction is a metaphor for life.

What’s the most challenging part of being an author?

I think the most challenging part is executing an idea. Ideas are everywhere. It’s not only coming up with an idea, but turning it into something in three-hundred fifty pages, that’s the challenge.

I understand you were a collegiate cross-country runner and a three-time Jeopardy champion. Will you tell us a few things about your life that readers would find interesting?

I have an overdeveloped trivia lobe in my brain. Jeopardy is the most fun you can have standing up, I’ll just say that. [Laughter].

Is it true that “UNSUB” will also be a CBS-TV series?

Yes, that’s true. It’s been bought by the people behind Justified and Masters of Sex. They are great at developing cool and exciting dramas. I’m very thrilled by it.

Who do you see playing Caitlin Hendrix?

Oh, no. I can’t answer that because everybody who reads UNSUB creates the character in their own mind. In a way, every reader is a casting director and I don’t want to take over that job.

If you could meet any two fictional characters in all of literature, who would they be, and why?

Dave Robicheaux from James Lee Burke’s series, because I’m in love with him [Laughter] My husband won’t appreciate that. And…Kinsey Millhone from Sue Grafton’s series because she’s from my hometown and would be a great friend. If I ever got in trouble, I’d have her to call.

Will you complete this sentence: “Writing novels has taught me___________?”

It’s taught me perseverance and patience. It’s taught me that we all have the possibility to be successful if we take the chance when it’s presented to us.

What’s coming next from Meg Gardiner?

Next is the sequel to UNSUB.

Congratulations on your career and on penning “UNSUB,” a novel Don Winslow compared to “The Silence of the Lambs” for its chilling plot, and about which he said, ‘The UNSUB, or Unknown Subject, at the heart of Meg Gardiner’s thriller is terrifying.’ I agree completely.

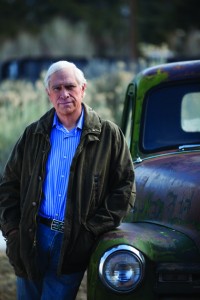

We know him as John Sandford, but that’s his nom de plume. As journalist John Camp, he won the 1986 Pulitzer Prize for his five-part series about an American farm family faced with an agricultural crisis. He eventually turned to writing thriller novels, and his twenty-fourth Prey novel, Field of Prey, featuring Lucas Davenport, will be available everywhere on May 5th, 2014. Lucas and his team must use all possible resources to try capturing an elusive killer or killers who claim at least twenty victims over a course of years.

We know him as John Sandford, but that’s his nom de plume. As journalist John Camp, he won the 1986 Pulitzer Prize for his five-part series about an American farm family faced with an agricultural crisis. He eventually turned to writing thriller novels, and his twenty-fourth Prey novel, Field of Prey, featuring Lucas Davenport, will be available everywhere on May 5th, 2014. Lucas and his team must use all possible resources to try capturing an elusive killer or killers who claim at least twenty victims over a course of years.