Real Stories About Real People Show Complexity of Mental Illness

A Hungarian-born man is found ranting in the street that he is “king of the Puerto Ricans.” A perfectly healthy woman feels compelled to undergo over a dozen operations. A man in a straightjacket somehow manages to commit suicide while inside a locked psychiatric ward.

ward.

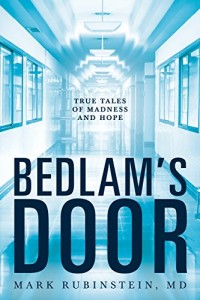

These are just a few of the compelling stories in Mark Rubinstein’s new book, Bedlam’s Door: True Tales of Madness and Hope. (You can read an exclusive excerpt here.) Rubinstein is a former practicing psychiatrist turned novelist who has drawn on his years of clinical experience to follow in the nonfiction footsteps of Oliver Sacks, shedding light on the complexities of the human mind with real stories about real people. Gizmodo sat down with him to learn more.

Gizmodo: What drove you to write this nonfiction book, after years of clinical practice and novel-writing?

Mark Rubinstein: It all came down to my wanting to tell the general public a little bit more about mental illness. When someone has a physical illness, people feel some kind of empathy, but they still respond to an obviously disturbed person with fear. It’s not just your heart, lung, or liver that’s sick—it is you. That is very threatening to people. And people don’t really understand the mental health dilemma, and the issues that mental health practitioners face.

Q: You brought a novelist’s sensibility to these stories, with composite characters and reconstructed dialogue. How much is fiction and how much is nonfiction?

Rubinstein: It is kind of a combination of fiction superimposed on a nonfictional layer of things that really happened. These were all real people and real cases—sometimes a composite of more than one person to protect their privacy. Oliver Sacks was accused of unwittingly giving away the identities of some of the people he wrote about in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

I never wanted to be accused of anything like that, so I changed everything: times, places, people, venues, even races. I didn’t even use a real hospital. Of course, I couldn’t remember all the dialogue from 30 years ago, but I created dialogue consistent with the story line. But these were all real stories and real people from people I had treated. There isn’t a story in there that isn’t true.

But the overarching theme running through most of the stories is that even with the most bizarre cases, if time is taken to listen to these people and understand their stories and background, perhaps we can offer them help. It’s all about storytelling. That’s what novelists do, and in a sense that’s what patients do when they come to see a psychiatrist: they tell a story.

Q: I was struck by your statement that even people who suffer from the same diagnosed condition can have very different stories.

Rubinstein: [Mental illness] can affect almost anybody, given certain circumstances. Some of the most successful people on the planet have a touch of hypomania. I know physicians and attorneys who don’t have full-blown manic episodes but they are filled with boundless energy. They are restless. They feel bored and unhappy unless they are facing a challenge. And they are highly successful. Take that to a more severe degree, however, and it can be completely disabling. And 100 different people can have 100 different pathways to the same diagnosable psychiatric disorder.

You contrast two very different examples of PTSD in the book, for instance.

Rubinstein: In one case, a police officer was shot while sitting in his patrol car outside a store near Tompkins Square Park in New York City. A bullet smashed through the windshield and hit him in the armpit, ruining his brachial plexus—a complicated series of nerves that serves the entire arm. He almost bled to death in the ride to the hospital, and he was crippled for the rest of his life. The depression, the PTSD, the pain he felt in his right arm—the pins and needles and tingling—was directly related to the psychic impact of that half-second of impact.

Then there is the man I call Nathan, found ranting on Delancy Street that he was the king of the Puerto Ricans. He was a carpenter, born in Hungary, and that skill saved his life at Auschwitz. He watched people disappear into the gas chambers—his family, his entire village. He was the sole survivor. But his PTSD didn’t develop until 40 years later, when he was in America and fell off the ladder while working on a roof, breaking some vertebrae in his back. He could no longer work and began having horrifying nightmares. It’s called delayed onset PTSD. So these two men came by totally different pathways to the same condition.

Q: In both your preface and conclusion, you talk about how mental illness has always been stigmatized throughout history. Is it really any different today?

Rubinstein: Well, today we don’t torture people. As recently as the 1950s, they were lobotomizing psychotic patients. They removed a good portion of the white matter of the frontal lobes of the cortex, and turned those people into—for lack of a better term—the walking dead. They became blunted and unresponsive to most emotional stimuli. It was done to try to improve their lot in life, but it shows how primitive things used to be.

When I was in resident psychiatry, the cops would drag a guy in and tell me, “This guy belongs in the loony bin, doc.” Even if the person was just drunk, they wanted to dump these people off in the psychiatric emergency room rather than take them to the precinct. They didn’t want to be bothered with an agitated, fulminating individual who was obviously disturbed.

What’s really changed is there is a much more scientific and compassionate approach. The popular conception of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) still exists from a famous scene in the 1974 movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest—Jack Nicholson with the bulging eyes and convulsions and coming out of it like a vegetable.

But they now use unipolar leads, and very low, slow pulse electricity. They administer muscle relaxants, so there is no convulsion. There is hardly any retrograde amnesia and what little there is resolves with a matter of days. It doesn’t take 12 to 18 sessions anymore, it only takes between four and six.

Q: You end on a somewhat surprising note of optimism, given that these are such very sad stories. I am curious about why you see hope for the future.

Rubinstein: No matter what kind of progress we make, there will always be people slipping through the cracks. There will always be people who either don’t want to be helped, or can’t be helped for some reason. But transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive new treatment that, so far at least, according to preliminary findings, has tremendously good effects—with no side effects or ingestion of chemicals.

Then there is the promise of gene therapy. At some point in the not too distant future, neuroscience will advance to the point where blood can be taken from a newborn child, and based on that baby’s genome, scientists will be able to predict what mental dysfunctions or illnesses that individual will have a predisposition for. Imagine if you could do that for people with a high risk of schizophrenia or severe bipolar disorder, based on the genome analysis of a two-day-old baby? It would put every psychiatrist out of business.

So in the long run, if the human race survives as a species, I think the prognosis medically [for mental illness] is very good. I am not sure that I am optimistic about the survivability of the human species, but I am optimistic in that limited way.

Matthew Palmer is a 24-year veteran of the U.S. Foreign Service. Having been at ground zero for many pressing global issues from Kosovo to Africa, he has extensive knowledge of international crises. His debut thriller, The American Mission, has been compared to John LeCarre’s The Constant Gardner. As a son of the late Michael Palmer, Matthew’s writing pedigree is clear.

Matthew Palmer is a 24-year veteran of the U.S. Foreign Service. Having been at ground zero for many pressing global issues from Kosovo to Africa, he has extensive knowledge of international crises. His debut thriller, The American Mission, has been compared to John LeCarre’s The Constant Gardner. As a son of the late Michael Palmer, Matthew’s writing pedigree is clear. Jon Land is the prolific author of more than thirty-five books. His thriller novels include the Caitlin Strong series about a fifth-generation Texas Ranger, and the Ben Kamal and Danielle Barnea books about a Palestinian detective and an Israeli chief inspector of police. He has also penned the Blaine McCracken series, standalone novels, and non-fiction. Jon was a screenwriter for the 2005 film Dirty Deeds. He is very active in the International Thriller Writers Organization.

Jon Land is the prolific author of more than thirty-five books. His thriller novels include the Caitlin Strong series about a fifth-generation Texas Ranger, and the Ben Kamal and Danielle Barnea books about a Palestinian detective and an Israeli chief inspector of police. He has also penned the Blaine McCracken series, standalone novels, and non-fiction. Jon was a screenwriter for the 2005 film Dirty Deeds. He is very active in the International Thriller Writers Organization.